ĐẠI CƯƠNG

- Điều trị lý tưởng ở bệnh nhân xơ gan mất bù là ngăn ngừa xơ gan tiến triển, không phải là điều trị biến chứng

- Điều trị tối ưu xơ gan mất bù chủ yếu nhằm vào những thay đổi bệnh lý trong gan với mục đích khôi phục lại tính toàn vẹn cấu trúc gan bằng cách

- ức chế viêm

- đẩy lùi xơ hóa

- cân đối tuần hoàn cửa và động mạch

- bình thường hóa số lượng và chức năng tế bào

Tế bào bị tổn thương Mô hình phân tử liên quan tổn thương

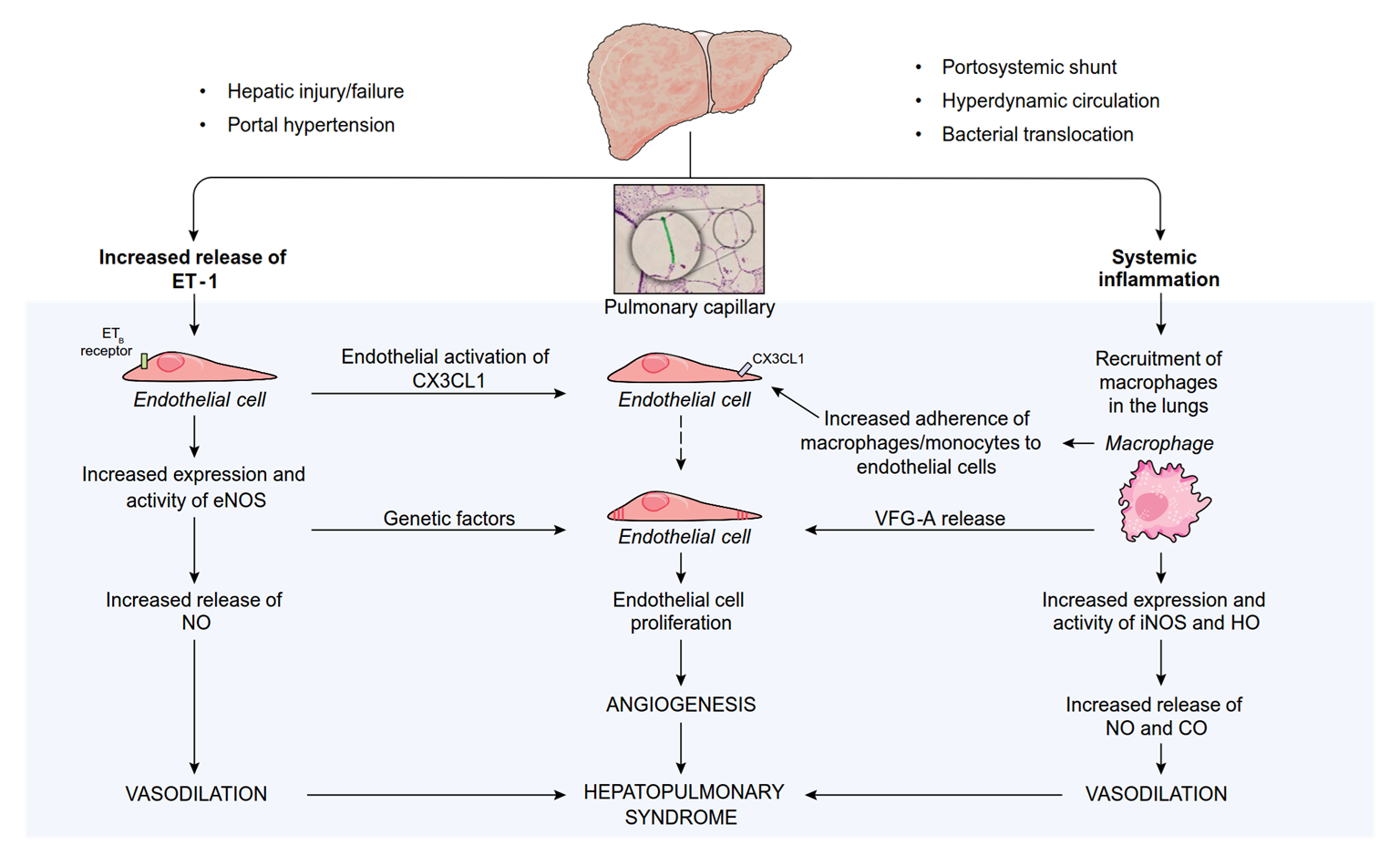

Những cơ chế

khác

Tăng áp cửa

Kích hoạt

thụ thể nhận dạng bẩm sinh

Sự chuyển chỗ vi khuẩn

Tổn thương gan

Phóng thích các phân tử tiền viêm

++

Giãn tiểu động mạch tạng, rối loạn chức năng tim mạch

năng thận

Rối loạn chức năng thượng thận

Sinh bệnh của xơ gan mất bù

Bernardi M. J Hepatol 2015;63:1272–1284

Xơ gan

Bệnh não gan Rối loạn chức

Hội chứng gan thận

Tổn thương thận cấp

Báng bụng

HCGT

Vàng da

Suy gan

Bệnh não gan

Xơ gan mất bù

Tăng áp cửa

Xơ gan

còn bù

XHTH

VPMNKNP

HCC

HCC

| 1 điểm | 2 điểm | 3 điểm | |

| Bệnh não gan Báng bụng

Bilirubin máu Albumin máu TQ kéo dài |

không không

< 2 mg/dl > 3,5 g/dl < 4’’ |

độ 1–2 ít 2–3

2,8–3,5 4–6” |

độ 3–4

trung bình, nhiều > 3 < 2,8 > 6” |

| Hoặc INR | < 1,7 | 1,7–2,2 | > 2,2 |

| XG ứ mật | Bili < 4 | 4–10 | > 10 |

KHẢ NĂNG SỐNG CÒN NGUY CƠ PHẪU THUẬT THEO CHILD-PUGH

| Child-Pugh | A | B | C |

| Điểm CTP | 5–6 | 7–9 | 10–15 |

| Tuổi thọ (năm) | 15–20 | 4–14 | 1–3 |

| Tử vong chu phẫu (%) | 10 | 30 | 80 |

Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis 2008

- EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2010;53:397–417

- Lach J, et al. Prognostic value of arterial pressure, endogenous vasoactive systems, and renal function in cirrhotic patients admitted to the hospital for the treatment of ascites. Gastroenterology 1988;94:482–487.

- Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis 2008

- Caregaro L, et al. Limitations of serum creatinine level and creatinine clearance as filtration markers in cirrhosis. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:201–205. 9

- Bernardi M, et al. The MELD score in patients awaiting liver transplant: strengths and weaknesses. J Hepatol 2011;54:1297–1306.

- Xơ gan có báng bụng tiên lượng xấu, tỷ lệ tử vong 1 và 2 năm ♯ 40 và 50%, theo thứ tự 1

- Hạ natri máu, huyết áp động mạch thấp, độ lọc cầu thận và bài tiết Na niệu thấp: yếu tố tiên lượng tử vong độc lập ở bệnh nhân xơ gan báng bụng 2

- Điểm Child-Pugh 3

- Mô hình bệnh gan giai đoạn cuối (MELD) 4

- Điểm MELD-Na và MELD-báng bụng 5

- Tùy thuộc biến chứng

- Điều trị chung xơ gan mất bù:

- Ngăn chặn các yếu tố căn nguyên

- Tác động lên các yếu tố đích của bệnh sinh mất bù và tiến triển của xơ gan

- Loại bỏ các yếu tố căn nguyên gây tổn thương gan

- Nền tảng quan trọng trong điều trị xơ gan

- Hiệu quả trong việc ngăn ngừa mất bù

- Cải thiện kết cục ở bệnh nhân xơ gan còn bù

10

ĐIỀU TRỊ XƠ GAN MẤT BÙ

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease.

Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. 69 j 154–181

- Các bước tiếp cận giảm tiến triển của xơ gan

- Cải thiện trục gan-ruột nhằm vào bất thường vi sinh vật và sự chuyển chỗ vi khuẩn bằng kháng sinh (rifaximin)

- Cải thiện chức năng tuần hoàn hệ thống bị rối loạn (albumin)

- Giảm tình trạng viêm (statin)

- Giảm tình trạng tăng áp cửa (thuốc chẹn beta)

- Điều trị triệu chứng và biến chứng

11

ĐIỀU TRỊ BÁNG BỤNG DO XƠ GAN

12

1. Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, et al. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology 2003;38:258–266.

2. Arroyo V, Gines P, Gerbes AL, Dudley FJ, Gentilini P, Laffi G, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of refractory ascites and hepato1r3enal

syndrome in cirrhosis. International Ascites Club. Hepatology 1996;23:164–176.

- Xơ gan bị báng bụng độ 2 hoặc 3 sống còn giảm

cân nhắc ghép gan khi xơ gan có báng bụng

- Báng bụng không biến chứng khi không bị

nhiễm trùng, kháng trị hoặc hội chứng gan thận

- Phân độ báng bụng

- Độ 1 – ít: phát hiện nhờ siêu âm

- Độ 2 – trung bình: bụng chướng vừa phải

- Độ 3 – lượng lớn: bụng chướng căng rõ

Chẩn đoán báng bụng

- Chọc dịch báng chẩn đoán tất cả bệnh nhân báng bụng độ 2 – 3 hoặc nhập viện vì báng bụng xấu hơn hoặc vì bất kỳ biến chứng nào của xơ gan

- Đo protein dịch báng để xác định nguy cơ VPMNKNP

- SAAG khi không rõ nguyên nhân báng bụng và/hoặc nghi ngờ nguyên nhân khác gây báng bụng

- Đếm tế bào để phân biệt báng bụng do bệnh ác tính

14

- Báng bụng độ 2 không biến chứng

- Nghỉ ngơi/giường có lợi trong điều trị báng bụng?

- Hạn chế natri

- Hạn chế natri vừa phải (80–120 mmol/ngày, tương ứng 4,6-6,9 g muối), tương đương với chế độ ăn không có muối và tránh các bữa ăn được chuẩn bị trước

- Tránh chế độ ăn có lượng natri rất thấp (<40 mmol/ngày) vì dễ bị các biến chứng do lợi tiểu và không tốt cho dinh dưỡng

- Hướng dẫn dinh dưỡng đầy đủ

- Báng bụng độ 2

- Thuốc lợi tiểu

- Báng bụng độ 2, lần đầu:

- Thuốc lợi tiểu

sử dụng 1 thuốc kháng mineralocorticoid

bắt đầu 100 mg/ngày, tăng dần 100 mg/ 72 giờ tối đa 400 mg/ngày nếu không đáp ứng

Nếu không đáp ứng ( cân <2 kg/tuần) hoặc kali máu, thêm furosemide 40 mg/ngày tăng dần đến tối đa 160 mg/ngày

-

-

- Báng bụng kéo dài/ tái phát: kháng mineralo- corticoid và furosemide, tăng liều tùy đáp ứng

- Đáp ứng furosemide kém, sử dụng Torasemide

-

- Báng bụng độ 2

- Thuốc lợi tiểu

- Giảm cân tối đa 0,5 kg/ngày nếu không phù và 1 kg/ngày nếu có phù

- Khi kiểm soát được báng bụng, nên giảm liều thuốc lợi tiểu đến mức thấp nhất có hiệu quả

- Trong những tuần đầu điều trị, cần theo dõi lâm sàng và sinh hóa máu thường xuyên, nhất là khi báng bụng lần đầu

- Thuốc lợi tiểu

- Báng bụng độ 2

- Ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu

- Ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu nếu: natri máu <125 mmol/L, TTTC, bệnh não gan xấu hơn / kéo dài, chuột rút

- Ngừng furosemide, nếu K+ máu <3 mmol/L

- Ngừng kháng mineralocorticoid, nếu K+ >6 mmol/L

- Truyền albumin hoặc baclofen (10 mg/ngày, mỗi tuần tăng 10 mg/ngày, đến 30 mg/ngày) đối với những bệnh nhân bị chuột rút

- Ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu

18

- Báng bụng độ 3 (lượng lớn)

- Chọc tháo dịch báng lượng lớn: xử trí hàng đầu đối với báng bụng lượng lớn, nên chọc tháo toàn bộ trong một lần duy nhất

- Chọc tháo dịch báng <5 lít, nguy cơ rối loạn tuần hoàn thấp. Chọc tháo dịch báng >5 L, nên tăng thể tích huyết tương bằng truyền albumin (8 g/L dịch báng), hiệu quả hơn so với các dịch tăng thể tích huyết tương khác

- Sau khi chọc tháo dịch báng, nên sử dụng lợi tiểu liều tối thiểu để ngăn ngừa báng bụng tái phát

- Chống chỉ định chọc tháo dịch báng

- Bệnh nhân không hợp tác

- Nhiễm trùng da vùng bụng tại vị trí chọc tháo

- Có thai

- Bệnh đông máu nặng (tăng tiêu sợi huyết hoặc đông máu nội mạch lan tỏa)

- Chướng ruột nặng

- Thuốc sử dụng đồng thời trong xơ gan báng bụng

- Không nên sử dụng NSAID vì có nguy cơ cao giữ natri, hạ natri máu và tổn thương thận cấp (TTTC)

- Không nên sử dụng các thuốc ức chế men chuyển angiotensin, đối kháng angiotensin II hoặc chẹn thụ thể α1-adrenergic vì tăng nguy cơ suy thận

- Không nên sử dụng kháng sinh aminoglycoside, vì tăng nguy cơ TTTC. Ngoại trừ trường hợp nhiễm khuẩn nặng không thể điều trị bằng các thuốc khác

- XGBB và chức năng thận bảo tồn, thuốc cản quang không liên quan đến tăng nguy cơ suy thận

| Định nghĩa | |

| Báng bụng kháng trị thuốc lợi tiểu

Diuretic-resistant ascites |

Báng bụng không cải thiện/ tái phát sớm vì thiếu đáp ứng với hạn chế natri và điều trị lợi tiểu |

| Báng bụng khó chữa với thuốc lợi tiểu

Diuretic-intractable ascites |

Báng bụng không cải thiện/ tái phát sớm vì có các biến chứng do thuốc lợi tiểu (ngăn cản việc sử dụng liều thuốc lợi tiểu hiệu quả) |

| Tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán | |

| Thời gian điều trị | Bệnh nhân phải điều trị lợi tiểu liều cao (spironolactone 400 mg/ngày và furosemide 160 mg/ngày) ít nhất một tuần và chế độ ăn muối <90 mmol/ngày |

| Thiếu đáp ứng | Giảm cân <0,8 kg/ 4 ngày và

lượng natri niệu < lượng natri ăn vào |

| Báng bụng tái phát sớm | Báng bụng độ 2 hoặc 3 tái phát trong vòng 4 tuần kể từ khi bắt đầu điều trị |

| Tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán Báng bụng kháng trị | |

| Biến chứng do thuốc lợi tiểu |

|

24

- Chọc tháo dịch báng lượng lớn lặp lại kèm albumin: điều trị hàng đầu đối với báng bụng kháng trị

- Nên ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu ở bệnh nhân báng bụng kháng trị bài tiết natri niệu ≤30 mmol /ngày

- Thận trọng khi sử dụng NSBB trong trường hợp báng bụng nặng hoặc kháng trị. Tránh sử dụng NSBB liều cao (propranolol >80 mg/ngày). Không khuyến cáo sử dụng carvedilol

NSBB: NonSelective Beta Blockers

- Bệnh nhân bị báng bụng kháng trị hoặc tái phát, hoặc chọc tháo không hiệu quả nên xem xét việc đặt shunt cửa chủ trong gan (TIPS)

- Đặt TIPS giúp cải thiện sống còn ở bệnh nhân báng bụng tái phát và cải thiện việc kiểm soát báng bụng ở bệnh nhân báng bụng kháng trị

- Sử dụng stent đường kính nhỏ, có phủ PTFE để giảm nguy cơ bệnh não gan và rối loạn chức năng do TIPS

- Thuốc lợi tiểu và hạn chế natri nên được tiếp tục sau đặt TIPS

TIPS: Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt

- TIPS không được khuyến cáo trong trường hợp

- Bilirubin huyết thanh >3 mg/dl

- Số lượng tiểu cầu <75 x 109/L,

- Bệnh não gan độ ≥2 hoặc bệnh não gan mạn

- Nhiễm trùng đang hoạt động

- Suy thận tiến triển

- Tăng áp phổi hoặc rối loạn chức năng tâm trương hoặc tâm thu nặng

ĐIỀU TRỊ

VIÊM PHÚC MẠC NHIỄM KHUẨN NGUYÊN PHÁT

28

Nguy cơ nhiễm khuẩn trong xơ gan do nhiều yếu tố

- Rối loạn chức năng gan

- Thông nối cửa chủ

- Mất cân bằng vi sinh vật ở ruột

- Tăng chuyển chỗ vi khuẩn

- Rối loạn chức năng miễn dịch do xơ gan

- Những yếu tố di truyền

- Chọc dịch báng chẩn đoán VPMNKNP ở BN XGBB

- Lúc nhập viện để loại trừ VPMNKNP

- Bị xuất huyết tiêu hóa, sốc, sốt, có những dấu hiệu nhiễm khuẩn toàn thân, triệu chứng tiêu hóa

- Tình trạng gan và thận xấu hơn, bệnh não gan

- Nghi ngờ VPMNK thứ phát nếu

- cấy dịch báng nhiều loại vi khuẩn

- số lượng bạch cầu trung tính rất cao

- nồng độ protein dịch báng cao

- hoặc đáp ứng kém với điều trị

- Đếm số lượng bạch cầu trung tính dịch báng >250

/mm3 là cần thiết để chẩn đoán VPMNKNP

- Cấy dịch báng tại giường không phải là điều kiện tiên quyết để chẩn đoán VPMNKNP, tuy nhiên giúp hướng dẫn điều trị kháng sinh

- Cấy máu nên được thực hiện ở tất cả bệnh nhân nghi ngờ VPMNKNP, trước khi điều trị kháng sinh

- Bệnh nhân bị du khuẩn báng (bạch cầu trung tính

<250/mm3, cấy (+)) có dấu hiệu nhiễm trùng hoặc đáp ứng viêm toàn thân nên điều trị kháng sinh.

Nếu không, phải chọc dịch lần hai. Cấy lần hai (+), bất kể số lượng bạch cầu, nên điều trị kháng sinh

Jalan R, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: a position statement based on

the EASL Special Conference. J Hepatol 2013;60:1310–1324

32

Phụ thuộc vùng: giống nhiễm trùng bệnh viện nếu xuất độ vi khuẩn kháng đa thuốc cao hoặc nhiễm trùng huyết

VPMNKNP

do chăm sóc y tế

Carbapenem đơn thuần hoặc phối hợp daptomycin, vancomycin hoặc linezold nếu xuất độ vi khuẩn gram + kháng đa thuốc hoặc nhiễm trùng huyết

VPMNKNP

bệnh viện

VPMNKNP: viêm phúc mạc nhiễm khuẩn nguyên phát MDRO: vi khuẩn kháng đa thuốc

Cephalosporin thế hệ 3 hoặc piperacillin- tazobactam

VPMNKNP

mắc phải ở cộng đồng

VPMNKNP

- Kháng sinh theo kinh nghiệm bắt đầu ngay lập tức.

- Kháng sinh theo hướng dẫn bởi đặc tính đề kháng của vi khuẩn

- VPMNKNP cộng đồng, tùy vùng:

Tỷ lệ kháng khuẩn thấp: cephalosporin 3

Tỷ lệ kháng khuẩn cao: piperacillin/tazobactam hoặc carbapenem

- VPMNKNP do chăm sóc y tế & bệnh viện, tùy vùng: Tỷ lệ kháng đa thuốc thấp: piperacillin/tazobactam Tỷ lệ cao vi khuẩn sinh lactamase: carbapenem Tỷ lệ vi khuẩn Gr (+) đa kháng thuốc cao, phối hợp carbapenem với glycopeptide hoặc daptomycin

hoặc linezolid

33

Jalan R, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: a position statement based on

the EASL Special Conference. J Hepatol 2013;60:1310–1324

- Kiểm tra hiệu quả của điều trị kháng sinh: xét nghiệm dịch báng lần hai tại thời điểm 48 giờ sau điều trị. Nghi ngờ thất bại điều trị kháng sinh nếu triệu chứng và dấu hiệu lâm sàng xấu hơn và/hoặc số lượng bạch cầu hoặc không giảm rõ (ít nhất 25%) sau 48 giờ

- Thời gian điều trị ít nhất 5-7 ngày

- Mủ màng phổi nguyên phát được điều trị tương tự viêm phúc mạc nhiễm khuẩn nguyên phát

- Albumin (1,5 g/kg lúc chẩn đoán và 1 g/kg vào ngày thứ 3) được khuyến cáo ở bệnh nhân bị VPMNKNP

34

Dự phòng tiên phát: bệnh nhân có protein dịch báng <15 g/L, không có tiền căn bị VPMNKNP

- Dự phòng tiên phát với norfloxacin (400 mg/ngày) ở bệnh nhân

- Child-Pugh ≥9 và bilirubin huyết thanh ≥3 mg/dl, chức năng thận giảm hoặc

- Hạ natri máu

- Ngừng dự phòng Norfloxacin ở bệnh nhân có cải thiện lâm sàng kéo dài và hết báng bụng

Bệnh nhân bị VPMNKNP: dự phòng tái phát

- Norfloxacin (400 mg/ngày, uống) cho bệnh nhân hồi phục sau VPMNKNP

- Rifaximin không được khuyến cáo thay thế norfloxacin để dự phòng VPMNKNP tái phát

- Sau đợt điều trị VPMNKNP

- không xác định

- hết báng bụng

- Bệnh nhân nguy cơ cao

- trong thời gian nằm viện

- Đang bị xuất huyết tiêu hóa

- 7 ngày

- Sau đợt điều trị VPMNKNP

- Sau đợt điều trị VPMNKNP

- Norfloxacin 400 mg/ngày

- Ciprofloxacin 500-1.000 mg/ngày

- Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole 960mg/ngày

- Đang bị XHTH

- Norfloxacin 400 mg X 2 lần/ngày X 7 ngày

- Ceftriaxone 1 g tiêm mạch/ngày X 7 ngày

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhos3is9.

Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. xxx

- PPI có thể làm tăng nguy cơ bị VPMNKNP, nên giới hạn sử dụng đối với người có chỉ định rõ

- NSBB có thể gây bất lợi cho bệnh gan giai đoạn cuối bị rối loạn huyết động, cần theo dõi sát và điều chỉnh liều hoặc ngừng thuốc nếu có chống chỉ định

- Probiotic: không có bằng chứng có lợi

- Bệnh nhân hồi phục sau VPMNKNP có sống còn kém, cần cân nhắc để ghép gan

PHÒNG NGỪA XUẤT HUYẾT TIÊU HÓA

DO VỠ TĨNH MẠCH GIÃN

40

XUẤT HUYẾT TIÊU HÓA

- North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med 1988;319:983–989.

- D’Amico G, et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: a 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:1180–1193.

- Augustin S, et al. Predicting early mortality after acute variceal hemorrhage based on classification and regression tree analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:1347– 1354. 41

- Bosch J, et al. Prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet 2003;361:952–954

- Tỉ lệ tử vong chung mỗi đợt xuất huyết do tĩnh mạch giãn 15%-25% vào tuần thứ sáu. Nguy cơ tử vong ở những người xuất huyết kèm biểu hiện mất bù khác (>80% ở thời điểm 5 năm) cao hơn nhiều so với xuất huyết do tĩnh mạch giãn là biến cố mất bù đơn độc (20% ở thời điểm 5 năm) 6,7

- Nguy cơ tử vong cao khi kèm TTTC, VPMNKNP 8

- Không phòng ngừa, xuất huyết tái phát 60%-70%, thường trong vòng 1-2 năm sau xuất huyết 9

Tiếp cận điều trị xuất huyết tiêu hóa cấp ở bệnh nhân xơ gan

Xuất huyết tiêu hóa cấp + Tăng áp cửa

Đánh giá ban đầu

![]()

![]()

Airway Breathing Circulation

Bồi hoàn thể tích bằng dung dịch tinh thể/keo) Truyền máu duy trì Hb 7 g/dl, mục tiêu 7-9 g/dl

Chèn bóng/đặt stent thực quản

nếu xuất huyết lượng lớn

Điều trị ngay: somatostatin, terlipressin

KS phòng ngừa: ceftriaxone, norfloxacine

Nội soi chẩn đoán sớm (<12 giờ) Xác định xuất huyết do tĩnh mạch giãn

Điều trị qua nội soi (thắt tĩnh mạch)

+ duy trì thuốc co mạch 3-5 ngày

và phòng ngừa kháng sinh

De Franchis R. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the BAVENO VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepa4t2ol

2015;63:743–752

Kiểm soát (~85%) Còn xuất huyết (~15%)

Cân nhắc TIPS sớm

TIPS cứu vãn

-

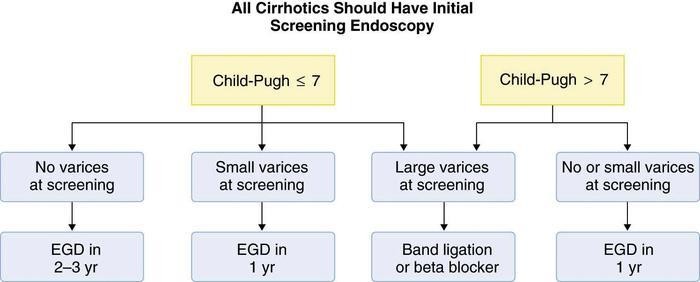

- Nội soi

- Thắt TMTQ

- Chích xơ TM phình vị

- Thuốc chẹn beta

- Nội soi

Nên nội soi thường qui

cho tất cả BNXG lần đầu

Child Pugh 7

Child Pugh > 7

Không giãn TM

Giãn TM nhỏ

Giãn TM lớn

Không, giãn nhỏ

NS: 2-3 năm

NS: 1 năm

Thắt, chẹn beta

NS: 1 năm

- Tĩnh mạch giãn nhẹ có dấu son hoặc Child-Pugh C điều trị NSBB (thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc)

- Tĩnh mạch giãn trung bình hoặc lớn điều trị NSBB hoặc thắt tĩnh mạch. Chọn lựa tùy khả năng tại chỗ, sự ưa thích của người bệnh, chống chỉ định và tác dụng phụ. NSBB có thể được ưa chọn hơn vì ngoài tác động giảm áp cửa còn có những tác động có lợi khác

- Báng bụng không phải là chống chỉ định sử dụng NSBB. Thận trọng trong những trường hợp báng bụng nặng hoặc kháng trị, tránh sử dụng NSBB liều cao, không sử dụng carvedilol

- Bệnh nhân bị hạ áp tiến triển (HAmax <90 mmHg) hoặc trong tình trạng cấp: xuất huyết, nhiễm trùng, VPMNKNP hoặc TTTC, ngừng NSBB

Sau khi hồi phục, có thể thử dùng lại. Nếu không dung nạp hoặc chống chỉ định NSBB hoặc có nguy cơ xuất huyết nên phòng ngừa xuất huyết bằng thắt tĩnh mạch giãn

-

- Phối hợp NSBB và thắt tĩnh mạch giãn giảm nguy cơ chảy máu tái phát tốt hơn so với đơn trị liệu

- Bệnh nhân không dung nạp NSBB, xem xét đặt TIPS, nếu không có chống chỉ định tuyệt đối

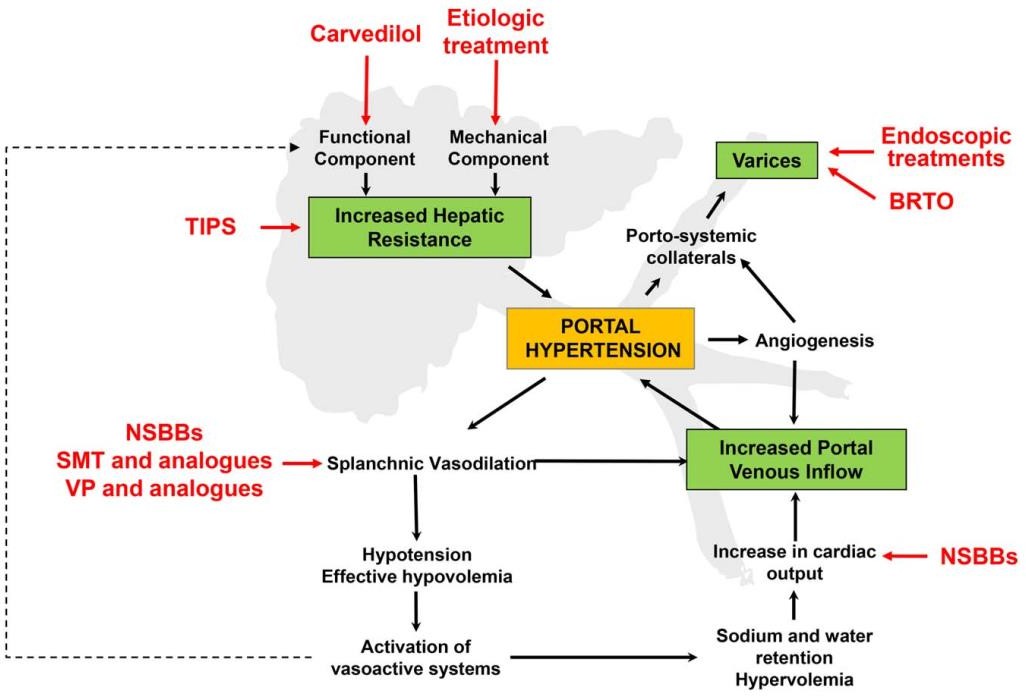

Cơ chế bệnh sinh Tăng áp cửa và

Vị trí hoạt động của các điều trị được khuyến cáo

AASLD 2017

46

46

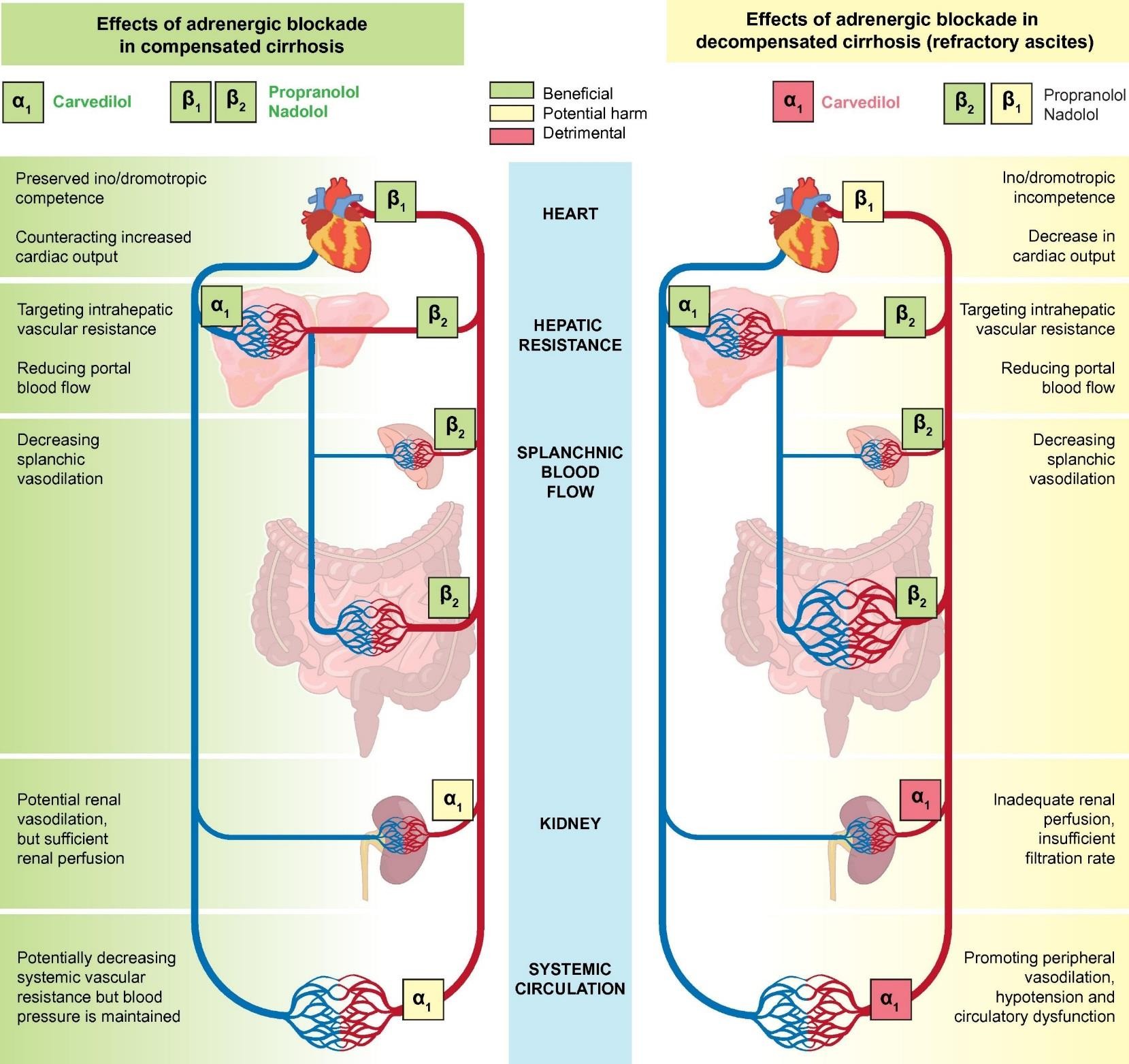

Cơ chế tác động của NSBB / XG còn bù Cơ chế tác động của NSBB / XG mất bù

Carvedilol

1

1 2

Propranolol Nadolol

có lợi

tiềm ẩn có hại có hại

1 Carvedilol

1 Propranolol

Nadolol

Mất khả năng ino/chomotropic

2

Chống lại tăng cung lượng tim

Nhằm vào kháng trở mạch máu trong gan

Bảo tồn ino/chomotropic

Kháng trở trong gan

Tim

Giảm cung lượng tim

Nhằm vào kháng trở mạch máu trong gan

Dòng máu đến tạng

Giảm giãn mạch tạng

Giảm giãn mạch tạng

DOI: (10.1

Giảm dòng máu cửa

Giảm dòng máu cửa

Thận

Tuần hoàn hệ thống

Kháng trở mạch máu hệ thống giảm tiềm tàng nhưng huyết áp được duy trì.

Tưới máu thận thiếu, tốc độ lọc không đủ

Giãn mạch thận tiềm tàng nhưng tưới máu thận đủ

EASL 2018

Giãn mạch ngoại biên, hạ áp và rối loạn chức năng tuần hoàn

ournal of Hepatology 2017 66, 859 016 2016.11.001)

Thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc

- ức chế thụ thể beta trên các mạch máu tạng

cung lượng tim, dòng máu tĩnh mạch cửa

áp tĩnh mạch cửa

- kháng trở bàng hệ quanh hệ cửa dòng máu bàng hệ

- xuất huyết khi nhịp tim 25% nhịp cơ bản

- nguy cơ xuất huyết tiên phát khoảng 50%

- khoảng 1/3 bệnh nhân không dung nạp thuốc

- không ngăn ngừa hình thành giãn tĩnh mạch

Thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc (NSBB) Chống chỉ định thuốc Propranolol

-

- Hen, bệnh phổi tắc nghẹn mạn (COPD)

- Nhịp tim chậm <50 lần/phút

- Hội chứng suy nút xoang

- Blốc nhĩ thất độ 2 hoặc 3

- Sốc, hạ huyết áp nặng

- Suy tim sung huyết không kiểm soát được

Thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc (NSBB) Dược động học thuốc propranolol

-

- Hấp thu nhanh & hoàn toàn

- Đạt nồng độ đỉnh 1-3 giờ sau uống

- Tăng hoạt tính sinh học khi bị suy gan

- Thời gian bán hủy 3-4 giờ

- Có ái lực với mô mỡ

- Chuyển hóa thành 4-hydroxypropranolol, có hoạt tính dược lý, thời gian bán hủy 5,2-7,2 giờ

Thuốc chẹn beta không chọn lọc (NSBB) Tác dụng phụ

-

- Buồn nôn, tiêu chảy

- Co thắt phế quản, khó thở

- Lạnh đầu chi, hội chứng Raynaud nặng hơn

- Chậm nhịp tim, hạ huyết áp, suy tim

- Mệt mỏi, chóng mặt, thị lực bất thường

- tập trung, ảo giác, mất ngủ, ác mộng

- Rối loạn chuyển hóa glucose & lipid

| Thuốc | Liều đầu/ngày | Liều điều trị/ngày |

| Propranolol * | 20-40 mg x 2 | 160 mg có báng bụng |

| 320 mg báng bụng (-) | ||

| Nadolol * | 20-40 mg | 80 mg có báng bụng |

| 160 mg báng bụng (-) | ||

| Carvedilol * | 6,25 mg | 6,25 mg x 2 |

- Garcia-Tsao G. Portal Hypertensive Bleeding in Cirrhosis. HEPATOLOGY, Vol. 65, No. 1,

2017. AASLD Practice Guidelines 2017

52

-

- Carvedilol không được khuyến cáo trong

- Phòng ngừa xuất huyết tái phát do tĩnh mạch giãn *

- Xơ gan báng bụng nặng hoặc kháng trị **

- Mục tiêu điều trị *

- Nhịp tim lúc nghỉ 55-60 lần/phút

- Huyết áp tâm thu không nên giảm <90 mmHg

- Carvedilol không được khuyến cáo trong

- Garcia-Tsao G. Portal Hypertensive Bleeding in Cirrhosis. HEPATOLOGY, Vol. 65, No. 1,

2017. AASLD Practice Guidelines 2017

** EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated

53

cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. xxx

ĐIỀU TRỊ

TỔN THƯƠNG THẬN CẤP TRONG XƠ GAN

54

Nam, 38 t, 50 kg, 4 ngày nay: tiêu chảy, sốt, báng bụng độ 3, đau vùng rốn, nhập BVĐK tỉnh: creatinine máu 1,3 mg/dL, tiểu 100 ml/6 giờ, chẩn đoán xơ gan mất bù, sau 24 giờ chuyển BVCR. Tại BVCR: creatinine máu 1,63 mg/dL. Chẩn đoán bệnh nhân bị tổn thương thận cấp dựa tiêu chuẩn nào?

0%

- Creatinine máu

- Lượng nước tiểu

- Creatinine máu và lượng nước tiểu

0%

0%

Tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán TTTC trong xơ gan

Angeli P et al. International Club of Ascites. Gut. 2015 Apr; 64(4):531-7

Thông số Định nghĩa

TTTC

Tăng Cr HT ≥26,4 μmoL/L (0,3 mg/dL) trong 48 giờ

hoặc tăng 50% so với giá trị nền

Thông số Định nghĩa

Cr HT nền Creatinine huyết thanh (Cr HT ổn định ≤3 tháng)

Nếu không có, trị số Cr HT gần nhất lần nhập viện này

Nếu trước đó không có, sử dụng Cr HT lúc nhập viện

TTTC: tổn thương thận cấp Cr HT: creatinine huyết thanh

Nam, 38 t, 4 ngày nay: tiêu chảy, sốt, báng bụng độ 3, đau vùng rốn, nhập BVĐK tỉnh: creatinine máu 1,3 mg/dL, chẩn đoán xơ gan mất bù, sau 24 giờ chuyển BVCR. Tại BVCR: creatinine máu 1,63 mg/dL. Bệnh nhân bị tổn thương thận cấp giai đoạn mấy?

0%

- 1

- 2

- 3

0%

0%

Tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán TTTC trong xơ gan

Angeli P et al. International Club of Ascites. Gut. 2015 Apr; 64(4):531-7

Thông số Định nghĩa

Cr HT nền Creatinine huyết thanh (Cr HT ổn định ≤3 tháng)

Nếu không có, trị số Cr HT gần nhất lần nhập viện này Nếu trước đó không có, sử dụng Cr HT lúc nhập viện

Tổn thương thận cấp giai đoạn

1 Tăng Cr HT ≥26,4 μmoL/L (0,3 mg/dL) hoặc tăng Cr HT ≥1,5–2 × giá trị nền

2 Tăng Cr HT >2–3 × giá trị nền

3 Tăng Cr HT >3 × giá trị nền hoặc

Cr HT ≥352 μmoL/L (4 mg/dL) có ↑ cấp ≥26,4 μmoL/L

hoặc bắt đầu điều trị thay thế thận

Cr HT: creatinine huyết thanh

Nam, 38 t, 4 ngày nay: tiêu chảy, sốt, báng bụng độ 3, đau vùng rốn, nhập BVĐK tỉnh: creatinine máu 1,3 mg/dL, chẩn đoán xơ gan mất bù, sau 24 giờ chuyển BVCR. Tại BVCR: creatinine máu 1,63 mg/dL, sau 48 giờ: creatinine máu 1 mg/dL. Đáp ứng điều trị của tổn thương thận cấp thuộc nhóm nào?

0%

- Không đáp ứng

- Đáp ứng một phần

- Đáp ứng hoàn toàn

0%

0%

Định nghĩa đáp ứng của TTTC

Angeli P et al. International Club of Ascites. Gut. 2015 Apr; 64(4):531-7

Đáp ứng điều trị

Không TTTC không thoái lui

Một phần

Giai đoạn TTTC thoái lui với Cr HT giảm ≤0,3

mg/dL so với giá trị nền

Hoàn toàn Giảm Cr HT >0,3 mg/dL so với giá trị nền

Định nghĩa

Cr HT nền Creatinine huyết thanh (Cr HT ổn định ≤3 tháng)

Nếu không có, trị số Cr HT gần nhất lần nhập viện này Nếu trước đó không có, sử dụng Cr HT lúc nhập viện

60

TTTC: tổn thương thận cấp Cr HT: creatinine huyết thanh

Nam, 38 t, 4 ngày nay: tiêu chảy, sốt, báng bụng độ 3, khó thở khi nằm, đau vùng rốn, nhập BVĐK tỉnh: creatinine máu 1,3 mg/dL, uống Aldacton 100 mg và furosemide 40 mg, chẩn đoán xơ gan mất bù, sau 24 giờ chuyển BVCR. Tại BVCR: creatinine máu 1,63 mg/dL, K+ 3 mEq/L, HA 120/80 mmHg. Điều trị nào sau đây thích hợp nhất?

0%

- Giảm liều lợi tiểu

- Ngừng lợi tiểu

- Ngừng lợi tiểu & truyền dịch

- thể tích huyết tương bằng truyền dịch

0%

0%

61

0%

Có

Đáp ứng

Không

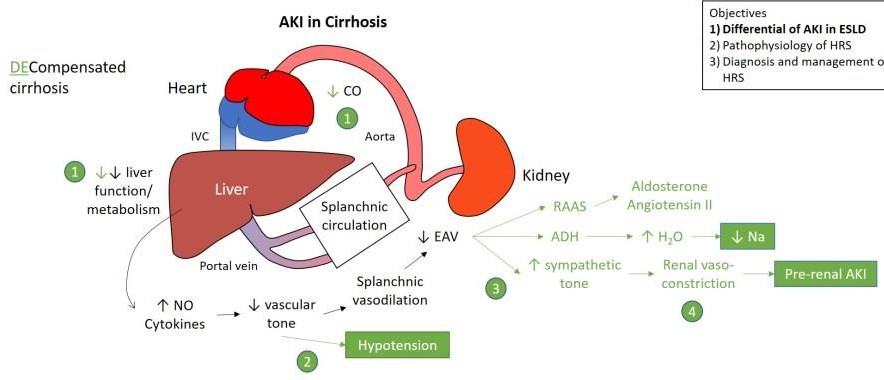

Tiếp cận điều trị TTTC ở bệnh nhân xơ gan

Angeli P, et al. J Hepatol 2015;62:968–974

TTTC giai đoạn 1

TTTC giai đoạn 2 và 3

- Theo dõi sát

- Loại bỏ yếu tố thúc đẩy (ngừng thuốc độc thận, thuốc giãn mạch, NSAID, giảm/ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu, điều trị nhiễm trùng)

- Tăng thể tích huyết tương, nếu có giảm thể tích

Ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu (nếu trước đó chưa ngừng) và tăng thể tích huyết tương bằng albumin (1 g/kg) trong 2 ngày

Thuốc co mạch và albumin

Điều trị đặc hiệu đối với thể TTTC

Tiếp tục điều trị TTTC

Có

Không

Theo dõi sát

Đáp ứng tiêu chuẩn HCGT

Tiến triển

Ổn định

Hồi phục

ĐIỀU TRỊ TỔN THƯƠNG THẬN CẤP

-

- Bù dịch tùy theo nguyên nhân và mức độ mất dịch

- Trường hợp không có nguyên nhân rõ của TTTC, TTTC giai đoạn >1A hoặc TTTC do nhiễm trùng, nên truyền albumin 20% liều 1 g albumin/kg trọng lượng cơ thể (tối đa 100 g) hai ngày liên tục

- Bệnh nhân TTTC và báng bụng lượng nhiều, chọc tháo dịch báng kèm truyền albumin ngay cả khi chọc tháo dịch báng lượng ít

63

Tiêu chuẩn chẩn đoán HCGT

Hội báng bụng quốc tế 2015

- Chẩn đoán xơ gan kèm báng bụng

- Chẩn đoán TTTC theo tiêu chuẩn TTTC của ICA

- Không đáp ứng sau 2 ngày liên tục ngừng thuốc lợi tiểu và tăng thể tích huyết tương = albumin 1 g/kg cân nặng

- Không sốc

- Không sử dụng các thuốc độc thận (NSAID, aminoglycoside, thuốc cản quang…)

- Không có dấu hiệu của tổn thương thận cấu trúc, như không có protein niệu (>500 mg/ngày), không có tiểu máu vi thể (>50 hồng cầu/quang trường phóng đại), thận bình thường trên siêu âm

Thuốc co mạch và albumin được khuyến cáo khi đủ tiêu chuẩn định nghĩa HCGT TTTC giai >1A

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. xxx

-

- Terlipressin và albumin được chọn hàng đầu trong điều trị HCGT. Telipressin tiêm thẳng tĩnh mạch liều đầu 1 mg mỗi 4-6 giờ hoặc truyền tĩnh mạch liều 2 mg/ngày. Trường hợp không đáp ứng (Cr huyết thanh giảm <25% so với giá trị đỉnh), sau 2 ngày, tăng liều terlipressin đến tối đa 12 mg/ngày

- Albumin 20% liều 20-40 g/ngày

Đo CVP hoặc các biện pháp khác đánh giá thể tích máu trung tâm, giúp ngăn ngừa quá tải tuần hoàn bằng cách tối ưu hóa cân bằng dịch và liều albumin

65

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. xxx

- Noradrenaline có thể là thuốc thay thế terlipressin. Sử dụng noradrenaline cần có đường truyền tĩnh mạch trung tâm

- Midodrine phối hợp octreotide là lựa chọn khi không có terlipressin hoặc noradrenaline, hiệu quả thấp hơn nhiều so với terlipressin

- Tác dụng phụ của terlipressin hoặc noradrenaline: thiếu máu cục bộ và biến cố tim mạch. Nên kiểm tra thường qui điện tâm đồ trước khi bắt đầu điều trị và theo dõi sát trong thời gian điều trị. Tùy loại và mức độ tác dụng phụ, thay đổi hoặc ngừng điều trị

66

PHÒNG NGỪA HỘI CHỨNG GAN THẬN

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated

cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. xxx

67

Khuyến cáo

- Albumin (1,5 g/kg lúc chẩn đoán và 1g/kg ngày thứ ba) được sử dụng cho người bị VPMNKNP để phòng ngừa hội chứng gan thận

- Norfloxacin (400 mg/ngày được sử dụng để phòng ngừa VPMNKNP phòng ngừa hội chứng gan thận

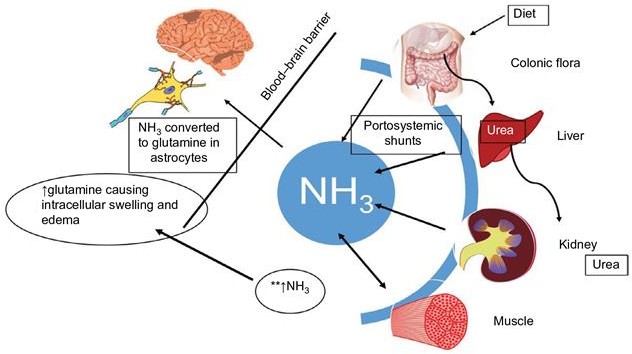

ĐIỀU TRỊ BỆNH NÃO GAN TRONG XƠ GAN

8

6

-

- Hội chứng rối loạn ý thức & thay đổi hoạt động thần kinh cơ

- Thường xảy ra ở trong suy tế bào gan cấp hoặc mạn hoặc có thông nối cửa chủ

- Cơ chế bệnh sinh còn tranh cãi &

có sự tham gia của nhiều chất trung gian

Phân độ bệnh não gan

- Độ I: thay đổi chu kì ngủ, hơi lú lẫn, dễ bị kích thích, run vẫy

- Độ II: ngủ lịm, mất định hướng, thái độ bất thường, run vẫy

- Độ III: lơ mơ, lú lẫn nặng, hung hăng, run vẫy

- Độ IV: hôn mê

Yếu tố thúc đẩy

- Tăng urê huyết

- Thuốc an thần, thuốc hướng tâm thần

- Dẫn xuất á phiện

- Xuất huyết tiêu hóa

- kali máu & kiềm máu (lợi tiểu, tiêu chảy)

- Chế độ ăn nhiều đạm, bón

- Nhiễm trùng

- Rối loạn chức năng gan tiến triển

- Thông nối cửa chủ (phẫu thuật, TIPS)

Chẩn đoán

-

- Biểu hiện đa dạng:

Thay đổi tâm thần kinh nhẹ hôn mê Run vẫy: bệnh não gan độ I-III,

triệu chứng không đặc hiệu

-

- EEG: sóng ba pha, chậm, biên độ cao

- Định lượng NH3 máu

không nhạy & không đặc hiệu

Mục tiêu điều trị

- Nhận biết & điều trị

nguyên nhân & yếu tố thúc đẩy

- Giảm sản xuất & hấp thu NH3 & các độc chất khác từ ruột:

- giảm & thay đổi đạm trong chế độ ăn

- thay đổi vi khuẩn đường ruột

- thay đổi môi trường đường ruột

- làm trống đường ruột

- Thay đổi dẫn truyền thần kinh

Điều trị yếu tố thúc đẩy

- Tránh sử dụng thuốc an thần

- Chống chỉ định Morphine, Paraldehyde

- Không sử dụng acid amin dạng uống

- Không dùng thuốc lợi tiểu

- Bổ sung kali

- Bổ sung kẽm

- XHTH: cầm máu, loại bỏ máu

Giảm sản xuất & hấp thu NH3

-

- Chế độ ăn

- Kháng sinh

- Lactulose

- Thụt tháo

Chế độ ăn

- Cơn cấp: đạm giảm còn 20 g/ngày

- Lượng calo >25-35 kcal/kg: miệng, tĩnh mạch

- Nếu hồi phục, tăng dần 10 g đạm /ngày

- Nếu tái phát, trở lại mức điều trị trước

- Đạm thực vật

- nếu không dung nạp đạm động vật

- ít sinh NH3, methionine, acid amin thơm

- nhuận trường hơn & tăng lượng chất xơ

- tăng sự hợp nhất & thải trừ nitơ qua phân

- gây đầy hơi, tiêu chảy & nhiều phân

Kháng sinh

- Neomycin sản xuất NH3 đường tiêu hóa Liều: 500-1000 mg mỗi 6 giờ

thụt giữ 100-200 mL dung dịch 1% Thời gian: 5-7 ngày

Phối hợp Lactulose có tác động hiệp lực 1-3% hấp thu, nguy cơ suy thận & độc tai

Kháng sinh

-

- Metronidazol 250 mg uống mỗi 6-8 giờ

- hiệu quả như neomycin

- độc tính trên hệ thần kinh trung ương

- Rifaximin

- không được hấp thu

- hiệu quả đối với bệnh não gan độ 1-3

- liều 400 mg uống 3 lần mỗi ngày

- Vancomycin 250mg X 4 /ngày

- sử dụng vancomycin khi kháng lactulose

- Metronidazol 250 mg uống mỗi 6-8 giờ

Lactulose

-

- -1,4-galactosido-fructose – dissacharide

- vi khuẩn ở ruột phân hủy thành a-xít lactic

- giảm pH của phân, phân có tính a-xít

- tăng khả năng thẩm thấu của đại tràng

- tạo thuận lợi cho sự phát triển của vi khuẩn lên men lactose

- ức chế vi khuẩn tạo NH3

- giảm quá trình ion hóa & hấp thu NH3

- rút ngắn diễn tiến bệnh của BNG sau XHTH

Lactulose

- Liều đầu: 15-45 ml uống 2-4 lần/ngày

- Liều duy trì điều chỉnh để

tiêu phân mềm 3-5 lần /ngày

- Không sử dụng khi liệt ruột, tắc ruột

- Tác dụng phụ

- đầy hơi, tiêu chảy, đau bụng

- tiêu chảy nặng: Na, K & kiềm máu

- thể tích máu , suy thận

Thụt tháo

- Bệnh não gan do bón:

giảm khi đi tiêu trở về bình thường

- Dịch thụt tháo: trung tính hoặc có tính acid để làm sự hấp thu NH3

- Thụt tháo bằng lactulose tốt hơn nước 300 mL lactulose + 700 mL nước nhỏ giọt

- Thụt tháo bằng MgSO4: tăng Mg máu

- Thụt tháo với Phosphate an toàn hơn Mg

Mục tiêu điều trị

Nhận biết & điều trị

nguyên nhân & yếu tố thúc đẩy

Giảm sản xuất, hấp thu NH3 & các độc chất khác từ ruột

- giảm & thay đổi đạm trong chế độ ăn

- thay đổi vi khuẩn đường ruột

- thay đổi môi trường đường ruột

- làm trống đường ruột Thay đổi dẫn truyền thần kinh

Thay đổi dẫn truyền thần kinh

- Benzoate natri & L-ornithine-L-aspartate

-

- Benzoate natri làm tăng bài tiết NH3 niệu

-

- L-ornithine-L-aspartate thúc đẩy gan loại NH3 kích thích hoạt động chu trình urea gan thúc đẩy tổng hợp glutamine

Thuốc: uống, tiêm tĩnh mạch

→ nồng độ NH3 & cải thiện bệnh não

Thay đổi dẫn truyền thần kinh

- Levodopa & Bromocriptine Bệnh não có thông nối cửa chủ

- Levodopa

tiền thân của Dopamine gây tình trạng thức tỉnh

-

- Bromocriptine

chất đối vận thụ thể Dopamine đặc hiệu cải thiện khả năng tâm thần & EEG

Thay đổi dẫn truyền thần kinh

- Flumazenil

- đối kháng thụ thể Benzodiazepine

cải thiện rõ tình trạng thần kinh & EEG

cải thiện rõ tình trạng thần kinh & EEG- thời gian hoạt động rất ngắn

Thay đổi dẫn truyền thần kinh

- Các a-xít amin chuỗi ngắn Xơ gan

Các AA chuỗi ngắn , các AA thơm

Tỉ lệ AA chuỗi ngắn / thơm

Truyền dịch AA chuỗi ngắn nồng độ cao

→ kết quả khác nhau, do khác biệt về: Thành phần của các dung dịch AA Cách sử dụng

Đối tượng nghiên cứu

Những biện pháp khác

- Các phương pháp hỗ trợ gan tạm thời

- phức tạp

- không thích hợp với BNG do xơ gan

- Ghép gan: trị liệu cuối cùng

Thuốc và độc chất Rượu bia Methotrexate Amiodarone Vitamin A

Bệnh do chuyển hóa/di truyền Nhiễm sắt

Bệnh Wilson

Thiếu alpha1-antitrypsin

Viêm gan thoái hóa mỡ không do rượu

Viêm gan virus ĐIỀU TRỊ NGUĐYa ÊnanNg đưNờnHg mÂậtNbẩm sinh

Virus viêm gan B (±) D

Virus viêm gan C

Bệnh tự miễn

Viêm gan tự miễn

Xơ gan ứ mật tiên phát

Teo hẹp đường mật

GÂY XƠBGệnhAxơNhóa nang

Bất thường về mạch máu Hội chứng Budd-Chiari Suy tim phải

Viêm đường mật xơ hóa tiên phát

Căn nguyên khác

Bệnh gan thoái hóa hạt

Hội chứng tắc nghẽn xoang

Giãn mạch máu xuất huyết di truyền Xơ hóa tĩnh mạch cửa idiopathic

88

ĐIỀU TRỊ XƠ GAN DO RƯỢU

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease.

Journal of Hepatology 2018 vol. 69 j 154–181

89

- Bệnh nhân xơ gan do rượu cần được khuyến cáo và khuyến khích để đạt được sự kiêng rượu hoàn toàn để giảm nguy cơ biến chứng và tử vong do gan

- Xác định và điều trị các yếu tố đồng thời, như béo phì và kháng insulin, suy dinh dưỡng, hút thuốc lá, quá tải sắt và viêm gan virus

- Sàng lọc và điều trị các biến chứng xơ gan nên được áp dụng đối với xơ gan do rượu

VIÊM GAN B MẠN TRÊN XƠ GAN CÒN BÙ

Xơ gan còn bù và lượng virus <2.000 IU/mL, nên được điều trị kháng virus để giảm nguy cơ mất bù, bất kể nồng độ ALT (AASLD 2018)

- Tenofovir và entecavir được ưu tiên vì hiệu lực và ít nguy cơ bị kháng thuốc, mất bù và tác dụng phụ nghiêm trọng. Thuốc kháng virus có hàng rào di truyền thấp với đề kháng không được khuyến cáo vì sự xuất hiện kháng thuốc có thể dẫn đến mất bù. TAF là thuốc kháng virus được ưu tiên bổ sung

- Peg‐IFN không chống chỉ định ở bệnh nhân xơ gan còn bù, nhưng NA an toàn hơn

- Nếu không điều trị, theo dõi tăng HBV DNA và/hoặc mất bù lâm sàng mỗi 3-6 tháng. Điều trị bắt đầu nếu xảy ra một trong hai

90

VIÊM GAN B MẠN TRÊN XƠ GAN CÒN BÙ

- ALT trong XG còn bù thường bình thường hoặc <2 lần so với giới hạn bình thường trên. ALT > 2 lần, tìm nguyên nhân khác ALT và nếu không tìm thấy, thì đó là chỉ định mạnh hơn cho điều trị kháng virus

- Chứng cứ hiện tại không cung cấp thời gian điều trị tối ưu. Nếu ngừng điều trị, theo dõi ít nhất 1 lần/3 tháng/ ít nhất 1 năm, cho phép phát hiện sớm sự phát triển của virus có thể dẫn đến mất bù

- XG còn bù và HBV-DNA cao (>2.000 U/mL) được điều trị theo các khuyến nghị cho viêm gan virus B mạn HBeAg (-) và HBeAg (+)

- Điều trị thuốc kháng virus không loại trừ được nguy cơ HCC, cần tiếp tục theo dõi HCC

91

VIÊM GAN B MẠN TRÊN XƠ GAN MẤT BÙ

XGMB HBsAg (+) được điều trị thuốc kháng virus vô thời hạn bất kể nồng độ HBV DNA, HBeAg hoặc ALT để giảm nguy cơ biến chứng do gan xấu đi (AASLD 2018)

- Entecavir và tenofovir là thuốc được khuyến cáo. TAF chưa được nghiên cứu trong XGMB, do đó hạn chế sử dụng TAF. TAF hoặc entecavir nên được xem xét ở bệnh nhân XGMB có rối loạn chức năng thận và/hoặc bệnh về xương

- Chống chỉ định Peg‐IFN ở XGMB do tính an toàn

- Cân nhắc ghép gan ở những người đủ điều kiện

- Theo dõi chặt chẽ để phát hiện tác dụng phụ của điều trị kháng virus: suy thận, nhiễm toan lactic

- Điều trị thuốc kháng virus không loại trừ được nguy cơ HCC, cần tiếp tục theo dõi HCC

92

Điều trị Viêm gan C (không hoặc có đồng nhiễm HIV) ở bệnh nhân xơ gan còn bù (Child-Pugh A) (EASL 2018)

| HCV | Điều trị trước | SOF/VEL | GLE/PIB | SOF/VEL

/VOX |

SOF/LED | GZR/EBR | OBV/PIV/ r+DSV |

| G1a | Không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần

(≤8.105 IU/ml) |

không |

| G1a | Có | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | không | không | |

| G1b | K/Có | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | 12 tuần |

| G2 | K/Có | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | không | không | không |

| G3 | K/Có | không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | không | không |

| G4 | Không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần (≤8.105 IU/ml) | không |

| G4 | Có | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | không | không | không |

| G5 | Không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | 12 tuần | không | không |

| G5 | Có | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | không | không | không |

| G6 | Không | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | 12 tuần | không | không |

| G6 | Có | 12 tuần | 12 tuần | không | không | không | không |

DSV: dasabuvir; EBR: elbasvir; GLE: glecaprevir; GZR: grazoprevir; LDV: ledipasvir; OBV: ombitasvir; PIB: pibrentasvir; PTV: paritaprevir; r: ritonavir; SOF: sofosbuvir; VEL: velpatasvir; VOX: voxilaprevir

93

94

KẾT LUẬN

Võ Thị Mỹ Dung [email protected] Bộ môn Nội tổng quát

XG là giai đoạn cuối của nhiều loại bệnh gan mạn

BN XGMB thường nhập viện & có nguy cơ cao bị tử vong do biến chứng

Điều trị lý tưởng ở giai đoạn mất bù là ngăn ngừa xơ gan tiến triển

, you can click on this to return to the outline or topics pages, depending on which section you are in

, you can click on this to return to the outline or topics pages, depending on which section you are in

1. Guyatt GH, et al. BMJ. 2008:336:924–6;

1. Guyatt GH, et al. BMJ. 2008:336:924–6;

*By shunting an intrahepatic portal branch into a hepatic vein

*By shunting an intrahepatic portal branch into a hepatic vein

*Provided that there are no absolute contraindications

*Provided that there are no absolute contraindications

Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:968–74;

Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:968–74;

Moreau R, et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–37;

Moreau R, et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–37;