Clinical Practice Guidelines

Decompensated

cirrhosis

These slides give a comprehensive overview of the EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of decompensated cirrhosis

- The guidelines were first presented at the International Liver Congress 2018 and are published in the Journal of Hepatology

Please feel free to use, adapt, and share these slides for your own personal use; however, please acknowledge EASL as the source

- Definitions of all abbreviations shown in these slides are provided within the slide notes

When you see a home symbol like this one:  , you can click on this to return to the outline or topics pages, depending on which section you are in

, you can click on this to return to the outline or topics pages, depending on which section you are in

These slides are intended for use as an educational resource and should not be used in isolation to make patient management decisions. All information included should be verified before treating patients or using any therapies described in these materials

- Please send any feedback to: [email protected]

- Chair

-

- Paolo Angeli

- Panel

- Càndid Villanueva, Claire Francoz, Rajeshwar P Mookerjee, Jonel Trebicka, Aleksander Krag,

Wim Laleman,

Pere Gines,

Mauro Bernardi (EASL Governing Board Representative)

- Reviewers

- Alexander Gerbes, Thierry Gustot, Guadalupe Garcia-Tsao

Methods

Grading evidence and recommendations

Grading evidence and recommendations

Grading is adapted from the GRADE system1

| Grade of evidence | |

| I | Randomized, controlled trials |

| II-1 | Controlled trials without randomization |

| II-2 | Cohort or case-control analytical studies |

| II-3 | Multiple time series, dramatic uncontrolled experiments |

| III | Opinions of respected authorities, descriptive epidemiology |

| Grade of recommendation | |

| 1 | Strong recommendation: Factors influencing the strength of the recommendation included the quality of the evidence, presumed patient-important outcomes, and cost |

| 2 | Weaker recommendation: Variability in preferences and values, or more

uncertainty: more likely a weak recommendation is warranted Recommendation is made with less certainty: higher cost or resource consumption |

1. Guyatt GH, et al. BMJ. 2008:336:924–6;

1. Guyatt GH, et al. BMJ. 2008:336:924–6;

EASL CPG decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018;doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024

Background

Definition and pathophysiology of decompensated cirrhosis

![]()

ACLF

Stage 6: late decompensation:

Refractory ascites, persistent PSE or jaundice,

infections, renal and other organ dysfunction

End stage

Death

- Transition from compensated cirrhosis to DC occurs at a rate of ~5–7% per year

- DC is a systemic disease, with multi-organ/system dysfunction

| Compensated |

| Stage 0: no varices, mild PH

LSM >15 and <20 or HVPG >5 and <10 mmHg |

| Stage 1: no varices, CSPH

LSM ≥20 or HVPG ≥10 mmHg |

| Stage 2: varices (=CSPH) |

| Decompensated |

| Stage 3: Bleeding |

| Stage 4:

First non-bleeding decompensation |

| Stage 5:

Second decompensating event |

- Transition from compensated cirrhosis to DC occurs at a rate of ~5–7% per year

- DC is a systemic disease, with multi-organ/system dysfunction

Stage 0: no varices, mild PH

LSM >15 and <20 or HVPG >5 and <10 mmHg

Stage 1: no varices, CSPH

LSM ≥20 or HVPG ≥10 mmHg

Stage 2: varices (=CSPH)

Stage 3: Bleeding

Stage 4:

First non-bleeding decompensation

Stage 5:

Second decompensating event

![]()

ACLF

Stage 6: late decompensation:

Refractory ascites, persistent PSE or jaundice,

infections, renal and other organ dysfunction

End stage

Median survival: 2 years

Symptomatic

Decompensated

Median survival: 12 years

Asymptomatic

Compensated

Death

Liver injury

Cirrhosis

![]() Damaged cells/DAMPs

Damaged cells/DAMPs

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

| Portal hypertension | |

| Bacterial translocation/PAMPs | |

Other potential mechanisms

Release of pro-inflammatory molecules (ROS/RNS)

Activation of innate pattern recognition receptors

++

Splanchnic arteriolar vasodilation and

cardiovascular dysfunction

Adrenal dysfunction

HE Kidney

dysfunction

HPS

Bernardi M, et al. J. Hepatol 2015;63:1272–84;

- Management of DC aims to improve outcomes of complications

Refractory

Ascites

Uncomplicated

Hepatic hydrothorax

CKD

AKI

Renal impairment

Hyponatremia

Complications of DC

Bacterial infections

ACLF

RAI

GI bleeding

![]()

PPHT

HPS

CCM

Cardiopulmonary

Increased understanding of DC pathophysiology permits the development of more comprehensive therapeutic and prophylactic approaches

to prevent or delay disease progression

Key recommendations

Overall management of DC

Click on a topic to skip

to that section

No treatment exists that can act on cirrhosis progression directly

- Two alternative approaches can be taken:

- Suppress aetiological factor(s) that cause liver inflammation and cirrhosis development

- Target key factors in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis decompensation and progression

Impact is variable

- Probably depends on the status of liver disease at the time

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| In patients with DC the aetiological factor should be removed, particularly alcohol consumption and hepatitis B or C virus infection, as this strategy is associated with decreased risk of decompensation and increased survival | II-2 | 1 |

Several strategies have been evaluated to prevent disease progression in patients with DC

-

- Targeting microbiome abnormalities and bacterial translocation to improve the gut–liver axis (i.e. rifaximin)

- Improving the disturbed circulatory function (i.e. long-term albumin)

- Treating the inflammatory state (i.e. statins)

- Targeting portal hypertension (i.e. β-blockers)

Further clinical research is needed to confirm the safety and potential benefits of these therapeutic approaches to

prevent cirrhosis progression in patients with DC

Most common complication of decompensation in cirrhosis

-

- Develops in 5–10% of patients with compensated cirrhosis per year

Significant impact on patients

-

- Impairs patient working and social life

- Frequently leads to hospitalization

- Requires chronic treatment

- Direct cause of further complications

- Poor prognosis (5-year survival, ~30%)

Ascites can be uncomplicated or refractory

-

- Ascites is uncomplicated when not infected, refractory or associated with impairment of renal function

Cirrhosis is responsible for 80% of cases of ascites

- Initial patient evaluation:

- History

- Physical examination

- Abdominal ultrasound

- Laboratory assessment

- Liver and renal function, serum and urine electrolytes, analysis of ascitic fluid

Ascites is graded based on amount of fluid in the abdominal cavity

| Grading of ascites* | |

| Grade 1 | Mild ascites: only detectable by ultrasound examination |

| Grade 2 | Moderate ascites: manifest by moderate symmetrical distension of abdomen |

| Grade 3 | Large or gross ascites: provokes marked abdominal distension |

*Ascites recurring on ≥3 occasions within a 12-month period despite dietary sodium restriction and adequate diuretic dosage are considered recurrent

Diagnostic paracentesis is indicated in:*

-

- All patients with new-onset grade 2 or 3 ascites

- Patients hospitalized for worsening ascites or any complication of cirrhosis

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Neutrophil count and culture of ascitic fluid culture† should be

performed to exclude bacterial peritonitis

|

II-2 | 1 |

| Ascitic total protein concentration should be performed to identify patients at higher risk of developing SBP‡ | II-2 | 1 |

| The SAAG should be calculated when the cause of ascites is not immediately evident, and/or when conditions other than cirrhosis are suspected§ | II-2 | 1 |

| Cytology should be performed to differentiate malignancy-related from non-malignant ascites | II-2 | 1 |

*Grade of evidence II-2, grade of recommendation 1; †Bedside inoculation blood culture bottles with 10 ml fluid each;

‡A total protein concentration <1.5 g/dl is generally considered a risk factor for SBP;

§SAAG ≥1.1 g/dl indicates that portal hypertension is involved in ascites formation with an accuracy of about 97%

Development of ascites in patients with cirrhosis is associated with a poor prognosis

-

- 1-year mortality: 40%

- 2-year mortality: 50%

Patients with ascites should be considered for referral for LT

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Since the development of grade 2 or 3 ascites in patients with cirrhosis is associated with reduced survival, LT should be considered as a potential treatment option | II-2 | 1 |

- Patients may not receive adequate priority in transplant lists

– Most commonly used prognostic scores can underestimate mortality risk

Improved methods to assess prognosis in these patients are needed

- Grade 1 or mild ascites

- No data on evolution and not known if treatment modifies natural history

- Grade 2 or moderate ascites

- Hospitalization not required

- Correct sodium imbalance:

- Dietary restriction and increased renal excretion with diuretics

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Moderate restriction of sodium intake (80–120 mmol/day,

corresponding to 4.6–6.9 g of salt) is recommended |

I | 1 |

| Generally equivalent to a no added salt diet with avoidance of

pre-prepared meals. Adequate nutritional education of patients on how to manage dietary sodium is also recommended |

II-2 | 1 |

| Very low sodium diets (<40 mmol/day) should be avoided | II-2 | 1 |

| Prolonged bed rest cannot be recommended | III | 1 |

Mainstay of medical treatment are anti-mineralocorticoid drugs*

- Loop diuretics may be added in patients with long-standing ascites

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

First episode of grade 2 ascites

|

I | 1 |

| In patients who do not respond to anti-mineralocorticoids† or who develop hyperkalaemia, furosemide should be added (from 40 mg/day with 40 mg stepwise increases to a maximum of 160 mg/day) | I | 1 |

Long-standing or recurrent ascites

|

I | 1 |

| Torasemide can be given in patients exhibiting a weak response to furosemide | I | 2 |

*Spironolactone, canrenone or K-canrenoate; †Body weight reduction <2 kg/week

Patients with cirrhosis and ascites are highly susceptible to rapid reductions in extracellular fluid volume

-

- Can lead to renal failure and hepatic encephalopathy

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

GI haemorrhage, renal impairment, hepatic encephalopathy, hyponatraemia, or alterations in serum potassium concentration, should be corrected before starting diuretic therapy

|

III | 1 |

| Diuretic therapy is generally not recommended in patients with

persistent overt hepatic encephalopathy |

III | 1 |

Loop diuretics can lead to potassium and magnesium depletion and hyponatraemia

- Muscle cramps can impair quality of life in patients receiving diuretics

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Frequent clinical and biochemical monitoring during the first weeks of treatment (particularly on first presentation) | I | 1 |

| Recommended maximum weight loss: 0.5 kg/day in patients without oedema, 1 kg/day in patients with oedema | II-2 | 1 |

| Once ascites have largely resolved, the dose of diuretics should be

reduced to the lowest effective dose |

III | 1 |

| Discontinue diuretics in case of severe hyponatraemia,* AKI, worsening hepatic encephalopathy, or incapacitating muscle cramps | III | 1 |

| Discontinue furosemide for severe hypokalaemia (<3 mmol/L ) Discontinue anti-mineralocorticoids for hyperkalaemia (>6 mmol/L) | III | 1 |

| Albumin infusion or baclofen administration† are recommended in

patients with muscle cramps |

I | 1 |

*Serum sodium <125 mmol/L; †10 mg/day, with a weekly increase of 10 mg/day up to 30 mg/day

- Grade 3 or large ascites

- LVP, under strict sterile conditions, is the treatment of choice

- Ascites should be completely removed in a single session*

- Contraindications to LVP include:

- Uncooperative patient, abdominal skin infection at puncture sites, pregnancy, severe coagulopathy, severe bowel distention

- LVP, under strict sterile conditions, is the treatment of choice

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| LVP should be followed with plasma volume expansion | I | 1 |

Plasma volume expansion should be performed by albumin infusion (8 g/L ascites)

|

I III | 1

1 |

| After LVP, patients should receive the minimum dose of diuretics

necessary to prevent re-accumulation of ascites |

I | 1 |

| When needed, LVP should be performed in patients with AKI or SBP | III | 1 |

*Grade of evidence I, grade of recommendation 1

- Patients with DC and ascites are at increased risk of renal impairment from several types of drug

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| NSAIDs should not be used (high risk of developing further sodium retention, hyponatraemia, and AKI) | II-2 | 1 |

| Angiotensin-converting enyzme inhibitors, angiotensin II antagonists, or 1-adrenergic receptor blockers should not generally be used (increased risk of renal impairment) | II-2 | 1 |

Aminoglycosides are discouraged (increased risk of AKI)

|

II-2 | 1 |

Contrast media

|

II III | 2

1 |

- International Ascites Club:

“Ascites that cannot be mobilized or the early recurrence of which

(after LVP) cannot be satisfactorily prevented by medical therapy”

Diuretic intractable

Diuretic resistant

Refractory ascites

Ascites that cannot be mobilized or the early recurrence of which cannot be prevented because of a lack of response to sodium

restriction and diuretic treatment

Ascites that cannot be mobilized or the early recurrence of which

cannot be prevented because of the development of diuretic-induced complications that preclude the use of an effective diuretic dosage

*Spironolactone 400 mg/day and furosemide 160 mg/day

Refractory ascites is associated with a poor prognosis

-

- Median survival around 6 months

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| The diagnosis of refractory ascites relies on the assessment of the

response of ascites to diuretic therapy and salt restriction

|

III | 1 |

| Patients with refractory ascites should be evaluated for LT | III | 1 |

LVP is a safe and effective treatment

-

- Should be associated with albumin administration to prevent PPCD

Drug treatments are controversial or inadequately studied

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Repeated LVP plus albumin (8 g/L of ascites removed) are recommended as first-line treatment for refractory ascites | I | 1 |

| Diuretics should be discontinued in patients with refractory ascites

who do not excrete >30 mmol/day of sodium under diuretic treatment |

III | 1 |

Although controversial data exist on the use of NSBBs in refractory ascites, caution should be exercised in severe cases*

>80 mg/day)

|

II-2 I | 1

2 |

*See also section on gastrointestinal bleeding

TIPS decompresses the portal system*

-

- Short term: accentuates peripheral arterial vasodilation

- Within 4–6 weeks: improves effective volaemia and renal function to increase renal sodium excretion

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Patients should be evaluated for TIPS insertion when:

|

I III | 1

1 |

TIPS insertion is recommended in patients:

|

I

I |

1

1 |

| The use of small-diameter PTFE-covered stents is recommended to reduce the risk of TIPS dysfunction and hepatic encephalopathy | I | 1 |

After TIPS insertion, continue the following until ascites resolution:

|

II-2 III | 1

1 |

*By shunting an intrahepatic portal branch into a hepatic vein

*By shunting an intrahepatic portal branch into a hepatic vein

Definition

-

- Accumulation of transudate in the pleural space

- In the absence of cardiac, pulmonary or pleural disease

- Ascites moves through small diaphragmatic defects

- Negative intrathoracic pressure induced by inspiration

- Can lead to respiratory failure

- Can be complicated by spontaneous bacterial infections (empyema)

- Associated with poor prognosis

- Median survival: 812 months

- Accumulation of transudate in the pleural space

Diagnosis

-

- Once pleural effusion has been ascertained, cardiopulmonary and

primary pleural diseases should be excluded*

-

- Diagnostic thoracentesis is required to rule out bacterial infection*

*Grade of evidence III, grade of recommendation 1

- First-line management relies on treatment of ascites with diuretics and/or LVP

- Not rare for pleural effusion to persist (refractory hepatic hydrothorax)

Therapeutic thoracentesis is required to relieve dyspnoea

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Patients with hydrothorax should be evaluated for LT | III | 1 |

| Diuretics and thoracentesis are recommended as the first-line management of hepatic hydrothorax | III | 1 |

| Therapeutic thoracentesis is indicated in patients with dyspnoea | III | 1 |

|

||

| frequent occurrence of complications | II-2 | 1 |

Hepatic hydrothorax:

beyond diuretics and thoracentesis

- Other treatments are appropriate in selected patients

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| In selected patients, TIPS insertion for recurrent symptomatic hepatic hydrothorax is recommended | II-2 | 1 |

Pleurodesis can be suggested to patients with refractory hepatic hydrothorax not amenable to LT or TIPS insertion

|

I | 2 |

Mesh repair of diaphragmatic defects is suggested for the management of hepatic hydrothorax in very selected patients

|

II-2 | 2 |

Common in patients with advanced cirrhosis

-

- Arbitrarily defined as serum sodium concentration <130 mmol/L

Hypo- and hypervolaemic hyponatraemia can occur

- Associated with:

- Increased mortality and morbidity, particularly neurological complications

- Reduced survival after LT

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Patients with cirrhosis who develop hyponatraemia should be evaluated for LT | II-2 | 1 |

| Removal of the cause and administration of normal saline are

recommended in the management of hypovolaemic hyponatraemia |

III | 1 |

| Fluid restriction* to 1,000 ml/day is recommended in the management of hypervolaemic hyponatraemia since it may prevent a further reduction in serum sodium levels | III | 1 |

*Beyond fluid restriction, hypertonic saline should be limited to rare patients with life-threatening complications. It can be considered in patients with severe hyponatraemia who are expected to undergo LT within days. Correction of serum sodium concentration after attenuation of symptoms should be slow (≤8 mmol/L per day) to avoid irreversible neurological sequelae (II-3;1). Albumin can be administered but data are very limited (II-3;2). Use of vaptans should be limited to clinical trials (III;1)

Occurs when variceal wall ruptures due to excessive wall tension

-

- Portal pressure is a key factor in both rupture and severity of bleeding

70% of GI bleeding events result from VH in patients with portal

hypertension

-

- Second most common decompensating event

- Most severe and immediate life threatening complication

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Patients with DC are at high risk and should have an OGD to screen for varices, unless previously diagnosed and treated | II-2 | 1 |

| If OGD is performed, the presence, size and presence of red wale marks should be reported | II-2 | 1 |

| In patients without varices in whom aetiological factor persists and/or

remain decompensated, screening OGD should be repeated yearly

|

III | 2 |

High risk of death when VH occurs in patients with DC

-

- Strategies to adequately treat VH and prevent (re)bleeding and death should be actively pursued

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Primary prophylaxis must be initiated upon detection of high-risk varices* because of increased risk of VH | I | 1 |

| Patients with small varices with red wale marks or Child–Pugh C

should be treated with NSBBs |

III | 1 |

| Patients with medium–large varices should be treated with either

NSBBs or EBL

pressure, they also exert other potential beneficial effects |

I III

II-2 |

1

2 2 |

*High-risk = small varices with red signs, medium or large varices irrespective of Child–Pugh classification or small varices in Child–Pugh C patients

NSBBs and EBL are equally effective in preventing first bleeding in patients with high-risk varices

-

- Choice between options depends on factors such as patient preference, contraindications or adverse events

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Ascites is not a contraindication for NSBBs. However, caution should be exercised in cases of severe or refractory ascites

|

I

II-2 I |

1

1 2 |

NSBBs should be discontinued in patients with progressive hypotension or those who develop an acute intercurrent condition* After recovery, reinstatement of NSBBs can be attempted

|

III

III III |

1

2 1 |

NSBBs and EBL in combination reduces the risk of re-bleeding compared with monotherapy

| Recommendation | ||

| Combination therapy of NSBBs + EBL is recommended | I | 1 |

| Covered TIPS placement is recommended in patients who continue to be intolerant to NSBBs* | III | 1 |

*Provided that there are no absolute contraindications

*Provided that there are no absolute contraindications

- Medical emergency: high rate of complications and mortality in DC

- Requires immediate treatment and close monitoring

![]()

![]() Acute GI bleed + portal hypertension Initial assessment* and resuscitation

Acute GI bleed + portal hypertension Initial assessment* and resuscitation

![]()

![]()

Early diagnostic endoscopy (<12 hours)

Confirm variceal bleeding

Endoscopic band ligation

Immediate start of vasoactive drug therapy† Antibiotic prophylaxis (I;1)‡

Airway Breathing Circulation

- Volume replacement with colloids and/or crystalloids should be initiated promptly (III;1)

Starch should not be used (I;1)

- Restrictive transfusion is recommended in most patients (Hb threshold, 7 g/dl; target range 7–9 g/dl) (I;1)

ENDOSCOPY

Balloon tamponade or oesophageal stenting

(if massive bleeding)

ENDOSCOPY

+

Maintain drug therapy for 3–5 days and antibiotics‡

Control

(~85% of cases)

Further bleeding

(~15% of cases)

Consider early TIPS in high risk patients Rescue with TIPS

*History, physical and blood exam, cultures; †Somatostatin/terlipressin; ‡Ceftriaxone (1 g/24 hours) is the first choice in patients with DC, those already on quinolone prophylaxis, and in hospital settings with high prevalence of quinolone-resistant bacterial infections. Oral quinolones (norfloxacin 400 mg BID) should be used in the remaining patients (I;1)

Figure adapted from de Franchis R, et al. J Hepatol 2015;63:74352;

Vasoactive drugs and ligation are the primary options for acute VH

-

- There may be a role for TIPS in selected high-risk patients

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| The combination of vasoactive drugs and ligation is recommended

as the first therapeutic option in acute variceal bleeding |

I | 1 |

Early pre-emptive covered TIPS (placed within 24–72 hours) can be suggested in selected high-risk patients, such as those with Child–Pugh class C with score <14

|

I | 2 |

- Up to 10–15% of patients have persistent bleeding or early re-bleeding

- Despite treatment with vasoactive drugs and EBL, and prophylactic antibiotics

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| TIPS should be used as the rescue therapy of choice in cases of persistent bleeding or early re-bleeding | I | 1 |

With the pre-requisite of expertise, balloon tamponade should be used in case of uncontrolled bleeding as a temporary ‘‘bridge” (max 24 hours) until definitive treatment can be instituted

|

III

I |

1

2 |

| In the context of bleeding, where encephalopathy is commonly encountered, prophylactic lactulose may be used to prevent encephalopathy, but further studies are needed | I | 2 |

| β-blockers and vasodilators should be avoided during the acute

bleeding episode |

III | 1 |

- Risk of bacterial infection in patients with cirrhosis is caused by multiple factors

- Liver dysfunction

- Portosystemic shunting

- Gut dysbiosis

- Increased BT

- Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction

- Genetic factors

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

-

- Definition: bacterial infection of ascitic fluid without any intra-abdominal surgically treatable source of infection

- Prevalence: all patients with cirrhosis and ascites are at risk

- 1.5–3.5% in outpatients; 10% in hospitalized patients

- Prognosis: mortality exceeded 90% when first described

- Reduced to ~20% with early diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis is based on diagnostic paracentesis

- 50% of SBP episodes are present at hospital admission

- Signs/symptoms of peritonitis: abdominal pain, tenderness, vomiting or

diarrhoea, ileus

-

- Signs of systemic inflammation: hyper- or hypothermia, chills, altered WBC count

- Worsening liver function, HE, shock, renal impairment, GI bleeding

However: SPB may be asymptomatic, particularly in outpatients

Diagnosis is based on diagnostic paracentesis

- 50% of SBP episodes are present at hospital admission

- Signs/symptoms of peritonitis: abdominal pain, tenderness, vomiting or

diarrhoea, ileus

-

- Signs of systemic inflammation: hyper- or hypothermia, chills, altered WBC count

- Worsening liver function, HE, shock, renal failure, GI bleeding

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Diagnostic paracentesis should be carried out in:

|

II-2 | 1 |

SBP diagnosed by a neutrophil count in ascitic fluid >250/mm3

|

II-2 | 1 |

| Ascitic fluid culture positivity is not a prerequisite for SBP diagnosis* | II-2 | 1 |

*Culture should be performed to guide antibiotic therapy (Grade of evidence II-2, grade of recommendation 1)

- Empirical IV antibiotics should be started immediately following diagnosis*

- Several factors should guide empirical antibiotic use†

- Environment (community acquired vs. nosocomial)

- Local bacterial resistance profiles

- Severity of infection

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Third-generation cephalosporins are recommended as first-line antibiotic treatment for community-acquired SBP in countries with low rates of antibiotic resistance

piperacillin/tazobactam or carbapenem should be considered |

I

II-2 |

1

1 |

| Antibiotic resistance is more likely in healthcare-associated and

nosocomial SBP

Enterobacteriaceae

|

I | 1 |

*Grade of evidence II-2, grade of recommendation 1; †Grade of evidence I, grade of recommendation 1

Antibiotic therapy should be carefully controlled and monitored

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Severe infections by XDR bacteria may require antibiotics known to be highly nephrotoxic in patients with cirrhosis (e.g. vancomycin or aminoglycosides)

accordance with local policy thresholds |

III | 1 |

| De-escalation according to bacterial susceptibility based on positive cultures is recommended to minimize resistance selection pressure | II-2 | 1 |

Antibiotic efficacy should be checked with a second paracentesis at 48 hours from starting treatment

|

II-2 | 1 |

| The duration of treatment should be at least 5–7 days | III | 1 |

| Spontaneous bacterial empyema should be managed similarly to SBP | II-2 | 2 |

- In patients with SBP treated with a third generation intravenous cephalosporin antibiotic, albumin significantly decreased the incidence of type-1 hepatorenal syndrome and reduced mortality1

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

The administration of albumin is recommended in patients with SBP

|

I | 1 |

- Sort P, et al. N Engl J Med 1999;341:403–9;

Patients with cirrhosis and low ascitic fluid protein concentration (<10 g/L) and/or high serum bilirubin levels are at high risk of developing a first episode of SBP1

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Primary prophylaxsis with norfloxacin (400 mg/day) is recommended in patients with:

|

I | 1 |

| Norfloxacin prophylaxis should be stopped in patients with long-lasting improvement of their clinical condition and disappearance of ascites | III | 1 |

-

- In patients who survive an episode of SBP, the cumulative recurrence rate at 1 year is approximately 70%1

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Prophylactic norfloxacin (400 mg/day, orally) is recommended in patients who recover from an episode of SBP | I | 1 |

| At present, rifaximin cannot be recommended as an alternative to

norfloxacin for secondary prophylaxis of SBP

|

I | 2 |

| Patients who recover from SBP have a poor long-term survival and

should be considered for LT |

II-2 | 1 |

| PPIs may increase the risk for the development of SBP, their use

should be restricted to those with a clear indication |

II-2 | 1 |

Non-SBP infections are frequent in patients with cirrhosis

-

-

- Associated with increased mortality

-

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Hospitalized patients with cirrhosis should be monitored closely

for the presence of infections to enable early diagnosis and treatment |

II-1 | 1 |

| Empirical antibiotic therapy should be commenced promptly | II-1 | 1 |

| Empirical antibiotic therapy should be based on: environment, local resistance profiles, severity and type of infection | I | 1 |

| In the context of high bacterial resistance to antibiotics, carbapenem alone or in combination with other antibiotics should be preferred* | I | 1 |

Severe infections by XDR bacteria may require antibiotics known to be highly nephrotoxic in patients with cirrhosis (e.g. vancomycin or aminoglycosides)

|

III | 1 |

| Routine use of albumin not recommended in infections other than SBP | I | 1 |

*Carbapenem alone or in combination with other antibiotics proved to be superior to third-generation

![]()

![]()

![]()

Good outcome

qSOFA and Sepsis-3 criteria have been validated in patients with cirrhosis1

-

-

- Can be used to assess severity of infection

-

Is baseline SOFA score available?

No

Yes

Apply sepsis-3 criteria and qSOFA

![]()

![]()

Poor outcome

Patient with need for transfer to ICU

Sepsis-3 positive and qSOFA negative

Good outcome

Sepsis-3 and qSOFA positive

Sepsis-3 and qSOFA negative

Negative

Positive

Apply sepsis-3 criteria

Grey zone Monitoring SOFA score is required

- Singer M, et al. JAMA 2016;315:801–10; Figure adapted from Piano S, et al. Gut 2017; doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314324.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Nosocomial

Healthcare- associated

Community- acquired

Other infections:

recommended empirical antibiotic treatment

Cellulitis

![]()

Piperacillin- tazobactam or 3rd-gen

cephalosporin + oxacillin

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs

or if sepsis

3rd-gen cephalosporin or meropemen + oxacillin or glycopeptides or daptomycin or linezolid

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Pneumonia UTI

Pneumonia UTI

![]()

![]()

Nosocomial

Healthcare- associated

Community- acquired

Nosocomial

Healthcare- associated

Community- acquired

Piperacillin- tazobactam

or ceftriaxone + macrolide or levofloxacin or moxifloxacin

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs

or if sepsis

Ceftazidime or meropemen + levofloxacin ± glycopeptides or linezolid

UNCOMPLICATED:

ciprofloxacin or cotrimoxazole

IF SEPSIS: 3rd-gen cephalosporin

or piperacillin-

tazobactam

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs

or if sepsis

UNCOMPLICATED:

fosfomycin or nitrofurantoin IF SEPSIS:

meropemen + teicoplanin or vancomycin

Other infections:

recommended empirical antibiotic treatment

Cellulitis

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Most clinically relevant

Most clinically relevant

3rd-gen cephalosporin or meropemen + oxacillin or glycopeptides or daptomycin or linezolid

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs

or if sepsis

Piperacillin- tazobactam or 3rd-gen

cephalosporin + oxacillin

Nosocomial

Healthcare- associated

Community- acquired

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() UTI

UTI

![]()

![]()

Pneumonia

Ceftazidime or meropemen + levofloxacin ± glycopeptides or linezolid

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs

or if sepsis

Piperacillin- tazobactam

or ceftriaxone + macrolide or levofloxacin or moxifloxacin

Nosocomial

Healthcare- associated

Community- acquired

Nosocomial

Healthcare- associated

Community- acquired

UNCOMPLICATED:

ciprofloxacin or cotrimoxazole

IF SEPSIS: 3rd-gen cephalosporin

or piperacillin-

tazobactam

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs

or if sepsis

UNCOMPLICATED:

fosfomycin or nitrofurantoin IF SEPSIS:

meropemen + teicoplanin or vancomycin

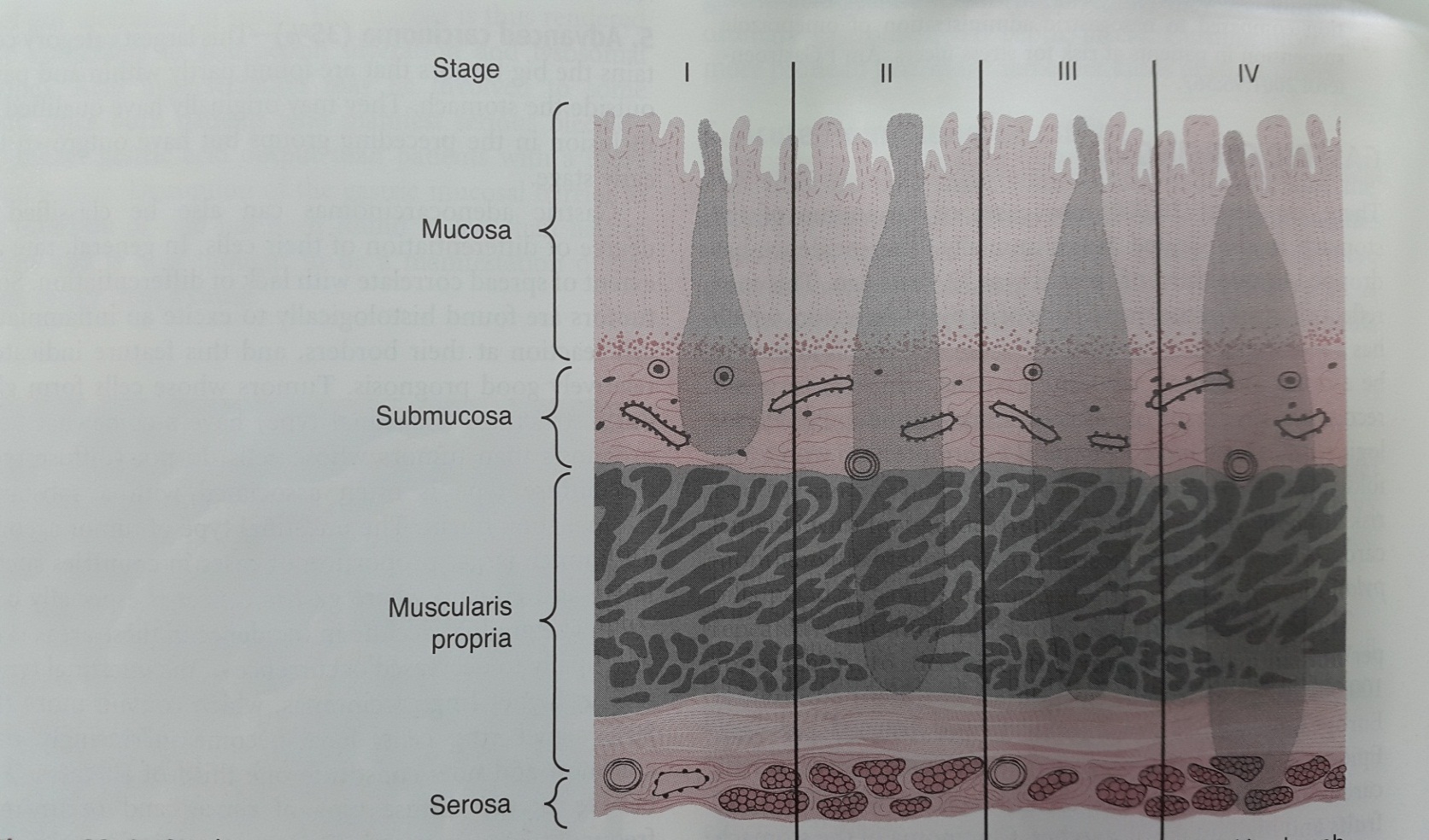

Definitions of renal impairment and staging of AKI have been updated

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| In patients with liver diseases, even a mild increase in SCr should be considered since it may underlie a marked decrease of GFR | II-2 | 1 |

| First step is to establish CKD, AKD, AKI or overlap | II-2 | 1 |

| Diagnosis of CKD should be based on a GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 estimated by SCr-based formulas, with or without signs of renal parenchymal damage* for at least 3 months | II-2 | 1 |

| The diagnostic process should be completed by staging CKD, which

relies on GFR levels, and by investigating its cause

|

II-2 | 1 |

Diagnosis of AKI should be based on adapted KDIGO criteria

48 hours, or an increase of ≥50% from baseline within 3 months |

II-2 | 1 |

| Staging of AKI should be based on an adapted KDIGO system† | II-2 | 1 |

-

- Definitions of renal impairment and staging of AKI have been updated

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| In patients with liver diseases, even a mild increase in SCr should be considered since it may underlie a marked decrease of GFR | II-2 | 1 |

| First step is to establish CKD, AKD, AKI or overlap | II-2 | 1 |

| Diagnosis of CKD should be based on a GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 estimated by SCr-based formulas, with or without signs of renal parenchymal damage* for at least 3 months | II-2 | 1 |

| The diagnostic process should be completed by staging CKD, which

relies on GFR levels, and by investigating its cause

|

II-2 | 1 |

Diagnosis of AKI should be based on adapted KDIGO criteria

48 hours, or an increase of ≥50% from baseline within 3 months |

II-2 | 1 |

| Staging of AKI should be based on an adapted KDIGO system† | II-2 | 1 |

KDIGO group definitions

| Definition | Functional criteria | Structural criteria |

| AKI | Increase in sCr ≥50% within 7 days,

OR increase in sCr ≥0.3 mg/dl within 2 days |

No criteria |

| AKD | GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73m2 for <3 months,

OR decrease in GFR ≥35% for <3 months, OR increase in sCr ≥50 % for <3 months |

Kidney damage

for <3 months |

| CKD | GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for ≥3 months | Kidney damage for ≥3 months |

-

- KDIGO group definitions

Increase in sCr ≥50% within 7 days,

OR

increase in sCr ≥0.3 mg/dl within 2 days

| Definition | Functional criteria | Structural criteria |

| AKI | Increase in sCr ≥50% within 3 months* | No criteria |

| AKD | GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73m2 for <3 months,

OR decrease in GFR ≥35% for <3 months, OR increase in sCr ≥50 % for <3 months |

Kidney damage

for <3 months |

| CKD | GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for ≥3 months | Kidney damage for ≥3 months |

*International Club of Ascites-recommended adaptation of KDIGO group criteria

| Subject | Definition | |||

| Baseline sCr |

|

|||

| Definition of AKI |

|

|||

| Staging of AKI |

acute increase ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) or initiation of renal replacement therapy |

|||

| Progression of AKI | Progression

Progression of AKI to a higher stage and/or need for RRT |

Regression

Regression of AKI to a lower stage |

||

| Response to

treatment |

No response No regression of AKI | Partial response

Regression of AKI stage with a reduction of sCr to ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) above baseline |

Full response

Return of sCr to a value within 0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) of baseline |

|

| Subject | Definition | |||

| Baseline sCr |

|

|||

| Definition of AKI |

|

|||

| Staging of AKI | Stage 1A (sCr <1.5mg/dl)*

Stage 1B (sCr ≥1.5mg/dl)* |

|||

acute increase ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) or initiation of renal replacement therapy |

||||

| Progression of AKI | Progression

Progression of AKI to a higher stage and/or need for RRT |

Regression

Regression of AKI to a lower stage |

||

| Response to

treatment |

No response No regression of AKI | Partial response

Regression of AKI stage with a reduction of sCr to ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) above baseline |

Full response

Return of sCr to a value within 0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) of baseline |

|

• Stage 1: increase in sCr ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5 µmol/L) or an increase in sCr ≥1.5-fold to 2- fold from baseline

*ICA recommended adaptations of KDIGO group criteria

![]()

Investigation and management should begin immediately

Investigation and management should begin immediately

Initial AKI* stage 1A

Initial AKI* stage >1A

![]()

NO

YES

Response

Does AKI meet criteria of HRS?

NO

YES

Specific treatment for

other AKI phenotypes

Vasoconstrictors and albumin

![]()

![]() *Initial AKI stage is defined as AKI stage at the time of first fulfilment of the AKI criteria;

*Initial AKI stage is defined as AKI stage at the time of first fulfilment of the AKI criteria;

Persistance

Further treatment of AKI decided on a case-by-case basics

Close follow-up

Progression

Resolution

Withdrawal of diuretics (if not yet applied) and volume expansion with albumin (1 g/kg) for 2 days

Close monitoring

Remove risk factors (withdrawal of nephrotoxic drugs, vasodilators and NSAIDs, taper/withdraw diuretics and β-blockers, expand plasma volume, treat infections† when diagnosed)

†Treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis should include albumin infusion according to current guidelines

-

- All types of AKI can occur in patients with cirrhosis

- Pre-renal, HRS, intrinsic, particularly ATN, and post-renal

- Key point is to differentiate HRS-AKI from ATN

- Classification of HRS was recently revised by the ICA1

- Type 1 HRS now corresponds to HRS-AKI

- Type 2 HRS includes renal impairment that fulfills the criteria of HRS but not of AKI (non-AKI-HRS or NAKI)

- All types of AKI can occur in patients with cirrhosis

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| It is important to differentiate among types of AKI in patients with

cirrhosis |

II-2 | 1 |

The diagnosis of HRS-AKI is based on revised ICA criteria (see next slide)

|

II-2 | 2 |

Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:968–74;

Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:968–74;

- Cirrhosis and ascites

- Diagnosis of AKI according to ICA-AKI criteria

- No response after 2 consecutive days of diuretic withdrawal and plasma volume expansion with albumin 1 g per kg of body weight

- Absence of shock

- No current or recent use of nephrotoxic drugs (NSAIDs, aminoglycosides, iodinated contrast media, etc.)

- No macroscopic signs of structural kidney injury,* defined as:

- Absence of proteinuria (>500 mg/day)

- Absence of microhaematuria (>50 RBCs per high power field)

- Normal findings on renal ultrasonography

*Patients who fulfil these criteria may still have structural damage such as tubular damage Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:96874;

First-line therapy is terlipressin plus albumin*

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| All patients meeting the current definition of HRS-AKI stage >1A

should be expeditiously treated with vasoconstrictors and albumin |

III | 1 |

Terlipressin can be administered by IV boluses (1 mg every 4–6 hours) or by continuous IV infusion (2 mg/day)†

|

I | 1 |

Albumin solution (20%) should be used at 20–40 g/day

|

II-2 | 1 |

Noradrenaline can be an alternative to terlipressin‡

|

I I I | 2

1 1 |

*Grade of evidence I, grade of recommendation 1;

†Continuous IV infusion allows for dose reduction to reduced adverse effects; ‡ Limited data are available

Management of HRS-AKI: screening and monitoring

Patients receiving treatment for HRS-AKI should be monitored for AEs and treatment response

-

-

- AEs related to terlipressin or noradrenaline include ischaemic and cardiovascular events

-

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Careful clinical screening including ECG before starting the treatment is recommended

Close monitoring of patients for the duration of treatment is important

type and severity of side effects |

I | 1 |

Response to treatment:

|

III | 1 |

| In case of recurrence a repeat course of therapy should be given | I | 1 |

*Continuous IV infusion allows for dose reduction to reduced adverse effects

In most patients with HRS-AKI TIPS is contraindicated because of severe degree of liver failure

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

There is insufficient data to advocate TIPS in HRS-AKI

|

II-2 | 2 |

| LT is the best therapeutic option for patients with HRS regardless of the response to drug therapy | I | 1 |

| The decision to initiate RRT should be based on the individual severity of illness | I | 2 |

The indication for liver-kidney transplantation remains controversial

|

II-2 | 1 |

-

- Based on the use of albumin in patients who develop SBP and the prevention of SBP using norfloxacin

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Albumin (1.5 g/kg at diagnosis and 1 g/kg on Day 3) should be given in patients with SBP to prevent AKI | I | 1 |

| Norfloxacin (400 mg/day) should be given as prophylaxis of SBP to prevent HRS-AKI | I | 1 |

Frequent occurrence in cirrhotic patients

-

-

- 30% of admitted patients and 25% of outpatients

-

Major cause of death in patients with cirrhosis (50% mortality rate)

-

- Develops on a background of acute decompensation

Characterized by hepatic and extrahepatic organ failure, highly activated systemic inflammation and a high 28-day mortality

-

- Precipitating events vary between populations and may include:

- Bacterial infections (3057% of cases)

- Active alcohol intake or alcohol binge

- Reactivation of HBV

- Superimposed HAV and HEV infection

- Precipitating events vary between populations and may include:

EASL-CLIF prognostic and diagnostic scores for ACLF

10 x [0.033 x Clif OFs + 0.04 x Age + 0.63 x Ln(WBC) – 2]

CLIF-C ACLF score for mortality prediction1*

| Chronic liver failure – organ failure score system1 | ||||

| Organ/system† | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | |

| Liver (bilirubin, mg/dl) | <6 | ≥6–<12 | ≥12.0 | |

| Kidney (creatinine, mg/dl) | <2.0 | ≥2.0–<3.5 | ≥3.5 or renal replacement | |

| Brain/HE (West Haven Criteria) | Grade 0 | Grades 1–2 | Grades 3–4‡ | |

| Coagulation (INR, PLT count) | <2.0 | ≥2.0–<2.5 | ≥2.5 | |

| Circulation (MAP, mmHg and

vasopressors) |

≥70 | <70 | Use of

vasopressors |

|

| Lungs | PaO2/FiO2, or | >300 | ≤300–>200 | ≤200§ |

| SpO2/FiO2 | >357 | >214–≤357 | ≤214§ | |

*Age in years, creatinine in mg/dL, WBC in 106 cells/L, sodium in mmol/L;

†Bold text indicates the diagnostic criteria for organ failures; ‡Patients submitted to mechanical ventilation due to HE and not to a respiratory failure were considered as presenting a cerebral failure (cerebral score = 3); §Other patients enrolled in the study with mechanical ventilation were considered as presenting a respiratory failure (respiratory score = 3)

- Jalan R, et al. J Hepatol 2014;61:1038–47;

Even mild renal or brain dysfunction in the presence of another organ failure, is associated with a significant short-term mortality and therefore defines the presence of ACLF

| Grades of ACLF | Clinical characteristics |

| NO ACLF | No organ failure, or single non-kidney organ failure, creatinine

<1.5 mg/dl, no HE |

| ACLF 1a | Single renal failure |

| ACLF 1b | Single non-kidney organ failure, creatinine 1.5–1.9 mg/dl and/or HE grade 1–2 |

| ACLF II | Two organ failures |

| ACLF III | Three or more organ failures |

Moreau R, et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–37;

Moreau R, et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1426–37;

Diagnosis of ACLF is based on organ failure in the presence of AD in patients with cirrhosis

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| ACLF diagnosis: cirrhosis and AD* plus organ failure(s) involving high short-term mortality | II-2 | 1 |

| Diagnosis and grading should be based using the CLIF-C Organ Failure score | II-2 | 1 |

Potential precipitating factor(s) should be investigated†

haemorrhage, surgery |

II-2 | 1 |

*Defined as the acute development or worsening of ascites, overt encephalopathy, GI haemorrhage, non-obstructive jaundice and/or bacterial infections; †Note that in a significant proportion of patients, a precipitant factor may not be identified

There is no specific therapy for ACLF

-

- Treatment is based on organ support and management of

complications

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Treatment of ACLF should be based on organ support, management

of precipitants and associated complications |

III | 1 |

| Patients should be treated in intermediate care or intensive care

settings |

III | 1 |

| ACLF is a dynamic condition and organ function should be

monitored frequently and carefully throughout hospitalization

|

III | 1 |

-

- The cause of liver injury can be treated in certain situations, e.g. HBV

- Early action is crucial to patient survival

- Treatment of precipitating factors

- Referral for LT before evolution of ACLF makes LT impossible

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Early identification and treatment of precipitating factors of ACLF, particularly bacterial infections, is recommended.

However, in some patients ACLF progresses despite treatment of precipitating factors |

III | 1 |

| Nucleoside analogues (tenofovir, entecavir) should be instituted as

early as possible in patients with HBV-related ACLF |

I | 1 |

| Early referral of patients with ACLF to LT centres for immediate

evaluation is recommended |

II-3 | 1 |

| Withdrawal of intensive care support after 1 week can be suggested

in patients who are not LT candidates and have ≥4 organ failures |

II-2 | 2 |

| Administration of G-CSF cannot be recommended at present | I | 2 |

- Inadequate cortisol response to stress in the setting of critical illness*

– Pathophysiology in cirrhosis is not well defined

- Diagnosis is influenced by the method used to measure cortisol

- It is not known whether cortisol supplementation in clinically stable cirrhosis with RAI is of any value

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Diagnosis of RAI

|

II-2 | 1 |

Salivary cortisol determination can be preferred

|

II-2 | 2 |

| Hydrocortisone treatment (at a dose of 50 mg/6 hours) of RAI

cannot be recommended |

I | 2 |

*Also known as critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI)

CCM occurs in patients with established cirrhosis characterized by:

-

-

- Blunted contractile response to stress (pharmacological/surgery or inflammatory)

- Altered diastolic left ventricular relaxation or/and increased left atrial volume

- Electrophysiological abnormalities e.g. prolonged QTc

- Cardiac output tending to decrease with decompensation

- Systolic dysfunction: LVEF <55%

-

CCM is largely subclinical but its presence influences prognosis in advanced disease

-

- Numerous electrocardiographic criteria, along with transmitral Doppler assessment, are used for the evaluation and diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction

- However, there is the need for more controlled studies and correlation with clinical endpoints

- Numerous electrocardiographic criteria, along with transmitral Doppler assessment, are used for the evaluation and diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

ECG in patients with cirrhosis should be performed with dynamic stress testing* (systolic dysfunction may be masked by hyperdynamic circulation and reduced afterload)

|

II-1 | 1 |

| Myocardial strain imaging and assessment of GLS may be useful in

the assessment of left ventricular systolic function in patients with DC |

II-2 | 2 |

| Cardiac MRI may identify structural changes | III | 2 |

Diastolic dysfunction may occur as an early sign of CCM in the setting of normal systolic function, and should be diagnosed using ASE criteria:

|

II-1 | 1 |

*Either pharmacologically, or through exercise; †And in the absence of influence of β-blockade

-

- Cardiac evaluation in patients with cirrhosis is important since CCM can influence prognosis

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| In patients with AD, reduced CO (as a manifestation of CCM) is associated with the development of AKI (specifically hepatorenal dysfunction) after infections such as SBP | II-1 | 1 |

QTc interval prolongation is common in cirrhosis and may indicate a poor outcome

|

II-2 | 2 |

Detailed functional cardiac characterization should be part of the assessment for

|

II-2 II-1 | 2

1 |

| Standardized criteria and protocols for the assessment of systolic and

diastolic function in cirrhosis are needed |

II-2 | 2 |

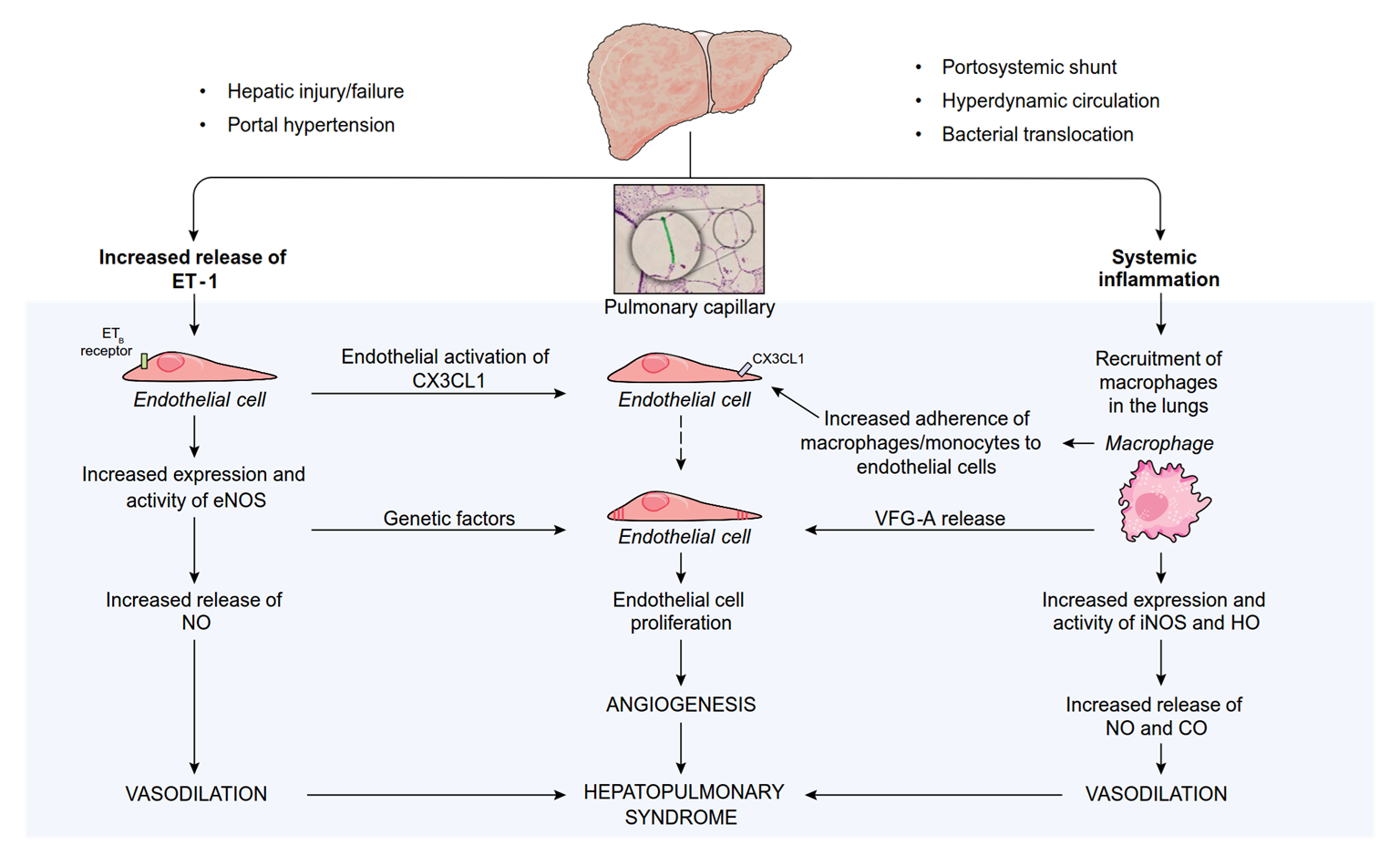

-

- Four main pulmonary complications may occur in patients with chronic liver disease

- Pneumonia

- Hepatic hydrotorax

- HPS

- Portopulmonary hypertension

- HPS is defined as a disorder in pulmonary oxygenation, caused by intrapulmonary vasodilatation and, less commonly, by pleural and pulmonary arteriovenous communications occurring in the clinical setting of portal hypertension

- Clinical manifestations of HPS in patients with chronic liver disease primarily involve dyspnoea and platypnoea

- Four main pulmonary complications may occur in patients with chronic liver disease

- Hepatic injury/failure

- Portal hypertension

- Portosystemic shunt

- Hyperdynamic circulation

- Bacterial translocation

Increased ET-1 release

ETB

Endothelial activation

receptor

Pulmonary capillary

CX3CL1

Systemic inflammation

Macrophage

Endothelial cell

of CX3CL1

Genetic

Increased eNOS

expression and activity

factors

Endothelial cell

Endothelial cell

Increased adherence

endothelial cells

monocytes to

of macrophages/

VFG-A release

recruitment

in the lungs

Endothelial cell

proliferation

Increased iNOS and HO

expression and activity

VASODILATION

ANGIOGENESIS

HEPATOPULMONARY SYNDROME

Increased NO

and CO release VASODILATION

-

- Hypoxia with partial pressure of oxygen <80 mmHg or alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient ≥15 mmHg in ambient air (≥20 mmHg in patients older than 65 years)

- Pulmonary vascular defect with positive findings on contrast-enhanced echocardiography or abnormal uptake in the brain (>6%) with radioactive lung-perfusion scanning

- Commonly in presence of portal hypertension, and in particular:

- Hepatic portal hypertension with underlying cirrhosis

- Pre-hepatic or hepatic portal hypertension in patients without underlying cirrhosis

- Less commonly in presence of:

- Acute liver failure, chronic hepatitis

- In patients with portal hypertension and the clinical suspicion of HPS partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) in ABG should be assessed

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| In patients with chronic liver disease, HPS should be suspected and investigated in presence of tachypnoea and polypnoea, digital clubbing and/or cyanosis | II-2 | 1 |

Screening in adults:

|

II-2 | 1 |

| The use of contrast (microbubble) echocardiography to characterize HPS is recommended | II-2 | 1 |

*For adults ≥65 years a P[A-a]O2 ≥20 mmHg cut-off should be used

-

- When PaO2 suggests HPS, further investigations are needed to determine the underlying mechanism

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| MAA scan should be performed to quantify the degree of shunting in patients with severe hypoxaemia and coexistent intrinsic lung disease, or to assess the prognosis in patients with HPS and very severe hypoxaemia (PaO2 <50 mmHg) | II-2 | 1 |

Neither contrast echocardiography nor MAA scan can definitively differentiate discrete arteriovenous communications from diffuse precapillary and capillary dilatations or cardiac shunts

|

II-2 | 1 |

| Trans-oesophageal contrast-enhanced echocardiography (although associated with risks) can definitively exclude intra-cardiac shunts | II-2 | 2 |

-

- There is no established medical therapy currently available for HPS, the only successful treatment for HPS is LT

| Recommendations for medical treatment Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Long-term oxygen therapy is recommended in patients with HPS and severe hypoxaemia despite the lack of available data concerning effectiveness, tolerance, cost effectiveness, compliance and effects on survival rates of this therapy | II-2 | 1 |

| No recommendation can be proposed regarding the use of drugs or the placement of TIPS for the treatment of HPS | I | 1 |

| Recommendations for liver transplantation | ||

| Patients with HPS and PaO2 <60 mmHg should be evaluated for LT since it is the only treatment for HPS that has been proven to be effective to date | II-2 | 1 |

| Severe hypoxaemia (PaO2 <45–50 mmHg) is associated with

increased post-LT mortality

|

II-2 | 1 |

-

- PPHT occurs in patients with portal hypertension in the absence of other causes of arterial or venous hypertension

- Classification is based on mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP), and assumes high pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and normal pulmonary occlusion pressures

- Mild: mPAP ≥25 and <35 mmHg

- Moderate: mPAP ≥35 and <45 mmHg

- Severe: mPAP ≥45 mmHg

- Incidence between 3–10% cirrhosis patients based on haemodynamic criteria; women are at 3x greater risk and it is more common in autoimmune liver disease

- There is no clear association between the severity of liver disease or portal hypertension and the development of severe PPHT

The evidence base for pharmacological therapies in PPHT is limited

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| Screening for PPHT should be via TDE in patients deemed

potential recipients for TIPS or LT

|

II-1 | 1 |

| In patients with PPHT who are listed for LT, echocardiography should be repeated on the waitlist (the specific interval is unclear) | III | 1 |

| β-blockers should be stopped and varices managed by endoscopic therapy in cases of proven PPHT | II-3 | 1 |

Therapies approved for primary pulmonary arterial hypertension may improve exercise tolerance and haemodynamics in PPHT

because of concerns over hepatic impairment |

II-2 | 1 |

| TIPS should not be used in patients with PPHT | II-3 | 1 |

-

- Although severe PPHT has, historically, been a contraindication for LT, the advent of improved haemodynamic control (with agents such as IV prostacyclin) allows LT to be considered

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| If mPAP <35 mmHg and right ventricular function is preserved, LT

should be considered

|

II-2 III | 1

1 |

| Therapy to lower mPAP and improve right ventricular function

should be commenced in patients with mPAP ≥35 mmHg

|

II-2 | 1 |

| MELD exception can be considered in patients with proven PPHT in whom targeted therapy fails to decrease mPAP <35 mmHg but does facilitate normalization of PVR to <240 dyn.s/cm-5 and right ventricular function | II-3 | 2 |

| MELD exception should be advocated in patients with proven PPHT of moderate severity (mPAP ≥35 mmHg) in whom targeted treatment lowers mPAP <35 mmHg and PVR <400 dyn.s/cm-5 | II-2 | 1 |

Additional recommendations

Portal hypertension gastropathy

-

- Often presents in patients with DC

- Natural history significantly influenced by the severity of liver disease and portal hypertension

- Often presents in patients with DC

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| NSBB and iron supplementation and/or blood transfusion, when indicated, are recommended as first-line therapy for chronic haemorrhage from PHG | I | 1 |

| In patients with transfusion-dependent PHG in whom NSBBs fail or are not tolerated, covered TIPS placement may be used in the absence of contraindications | II-3 | 2 |

| Acute PHG bleeding may be treated with somatostatin analogues or terlipressin but substantiating data are limited | I | 2 |

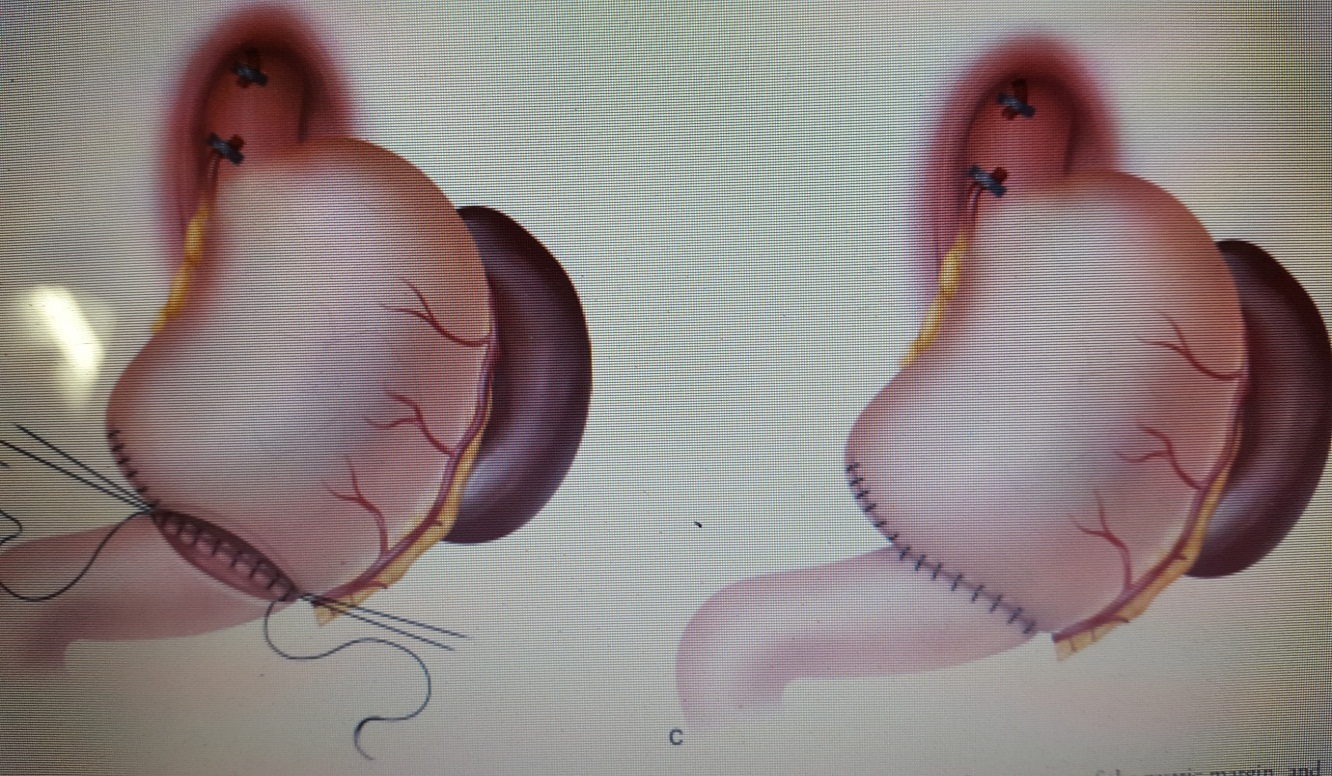

Gastric varices: classification, prevalence and risk

-

- The Sarin classification is most commonly used for risk stratification and management of gastric varices

| Type Definition | Relative frequency | Overall bleeding risk without treatment | |

| Gastro-oesophageal varices (GOV) | |||

| GOV type 1 | OV extending below cardia into lesser curvature | 70% | 28% |

| GOV type 2 | OV extending below cardia into fundus | 21% | 55% |

| Isolated gastric varices (IGV) | |||

| IGV type 1 | Isolated varices in the fundus | 7% | 78% |

| IGV type 2 | Isolated varices else in the stomach | 2% | 9% |

-

- Gastric varices are present in about 20% of patients with cirrhosis

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

| NSBBs are suggested for primary prevention of VH from GOV type 2 or IGV type 1 | III | 2 |

| Primary prevention for GOV type 1 follows the recommendations of oesophageal varices | III | 2 |

Acute gastric VH should be treated medically, like oesophageal VH

|

I

I |

1

2 |

| TIPS with potential embolization efficiently controls bleeding and prevents re-bleeding in fundal VH (GOV type 2 or IGV type 1) and should be considered in appropriate candidates | II-2 | 1 |

| Selective embolization (BRTO/BATO) may also be used to treat bleeding from fundal varices associated with large gastro/splenorenal collaterals, although more data is required | III | 2 |

Both neutrophil count and culture results should be taken into account

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Patients with bacterascites (neutrophil count <250/mm3 but positive bacterial culture) exhibiting signs of systemic inflammation or infection should be treated with antibiotics

the neutrophil count, the patient should be treated |

II-2

III |

1

1 |

Spontaneous bacterial pleural empyema diagnosed by:

|

II-2 | 1 |

Secondary bacterial peritonitis should be suspected in case of multiple organisms on ascitic culture, very high ascitic neutrophil count and/or high ascitic protein concentration, or in those patients with an inadequate response to therapy

|

III | 1 |

SBP or SBE

![]()

Nosocomial SBP or SBE

Healthcare-associated SBP or SBE

Community-acquired SBP or SBE

3rd-gen cephalosporin or

piperacillin-tazobactam

AREA DEPENDENT:

Like nosocomial infections if high prevalence of MDROs or if sepsis

Carbapenem alone or + daptomycin, vancomycin (or linezolid*) if high prevalence of MDR Gram+ bacteria or sepsis

*In areas with a high prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci Adapted from Jalan R, et al. J Hepatol 2014;60:1310–24;

Investigation and management should begin immediately

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Investigate AKI cause as soon as possible to prevent AKI progression

|

II-2 | 1 |

| Diuretics and/or β-blockers as well as other drugs that could be associated with the occurrence of AKI such as vasodilators, NSAIDs and nephrotoxic drugs should be immediately stopped | II-2 | 1 |

| Volume replacement should be used in accordance with the cause and severity of fluid losses | II-2 | 1 |

In case of no obvious cause of AKI, AKI stage >1A or infection-induced AKI:

|

III | 1 |

| In patients with AKI and tense ascites, therapeutic paracentesis should be associated with albumin infusion even when a low volume of ascitic fluid is removed | III | 1 |

-

- HRS-NAKI has an impaired response to vasorestrictors

| Recommendation Grade of evidence Grade of recommendation | ||

Vasoconstrictors and albumin are not recommended the treatment of HRS outside the criteria of AKI (HRS-NAKI)*

HRS-NAKI, but recurrence after withdrawal of treatment is the norm, and controversial data exist on the impact of the treatment on long-term clinical outcome, particularly from the perspective of LT |

I | 1 |

*Formerly known as HRS type II

Previous CLIF prognostic and diagnostic scores

10 x [0.03 x Age + 0.66 x Ln(Creatinine) + 1.71 x Ln(INR) + 0.88 x

Ln(WBC) 0.05 x Sodium + 8]

CLIF-C Acute decompensation score1*

| Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score | |||||

| Organ/system* | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Liver (bilirubin mg/dl) | <1.2 | ≥1.2–<2.0 | ≥2.0–<6.0 | ≥6.0–<12.0 | ≥12.0 |

| Kidney (creatinine mg/dl) | <1.2 | ≥1.2–<2.0 | ≥2.0–<3.5 | ≥3.5–<5.0 | ≥5.0 |

| Cerebral (HE grade) | NO HE | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III | Grade IV |

| Coagulation

(INR and PLT count) |

<1.1 | ≥1.1–<1.25 | ≥1.25–<1.5 | ≥1.5–<2.5 | ≥2.5 or PLT

≤20,000/mm3 |

| Circulation

(MAP mmHg and vasopressors†) |

≥70 | <70 | Dopamine ≤5 or dobutamine or terlipressin | Dopamine >5

or A ≤0.1 or NA ≤0.1 |

Dopamine >15

or A >0.1 or NA >0.1 |

| Lungs | |||||

| PaO2/FiO2, or | >400 | >300–≤400 | >200–≤300 | >100–≤200 | ≤100 |

| SpO2/FiO2 | >512 | >357–≤512 | >214–≤357 | >89- ≤214 | ≤89 |

*Bold text indicates the diagnostic criteria for organ failures; †μg/kg/min

, you can click on this to return to the outline or topics pages, depending on which section you are in

, you can click on this to return to the outline or topics pages, depending on which section you are in Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:968–74;

Angeli et al. J. Hepatol 2015;62:968–74;